Plankton in Antarctica

Plankton in Antarctic waters play a critical role in the Southern Ocean ecosystem. Divided into two primary categories, phytoplankton and zooplankton, they form the base of the Antarctic food web, directly supporting higher trophic levels, including fish, seabirds, and marine mammals.

Phytoplankton, as primary producers, convert sunlight into energy, while zooplankton, as primary consumers, feed on phytoplankton and other small particles, passing energy up the food web. Antarctic plankton exhibit unique adaptations to survive the cold, nutrient-rich waters, and extreme seasonal variability in light.

Phytoplankton

Phytoplankton are autotrophic organisms that photosynthesise to produce energy, making them the foundational producers in the marine food web. The primary groups in Antarctic waters include diatoms, dinoflagellates, and coccolithophores, each adapted to the unique conditions of these polar regions.

Diatoms (Diatoma)

Appearance and Size

Diatoms have silica-based cell walls, forming intricate glass-like frustules that help maintain buoyancy. They range from 2 to 200 micrometres.

Behaviour

Diatoms are mostly passive drifters, forming dense blooms in spring and summer as sunlight increases. They are adapted to nutrient-rich surface waters.

Reproduction Cycle

Diatoms primarily reproduce asexually by binary fission, though periodic sexual reproduction restores cell size.

Habitat and Range

They are found in surface waters throughout the Southern Ocean, especially around the Antarctic Peninsula and Ross Sea, where seasonal nutrient upwellings occur. They are also common in meltwater zones along the ice edge.

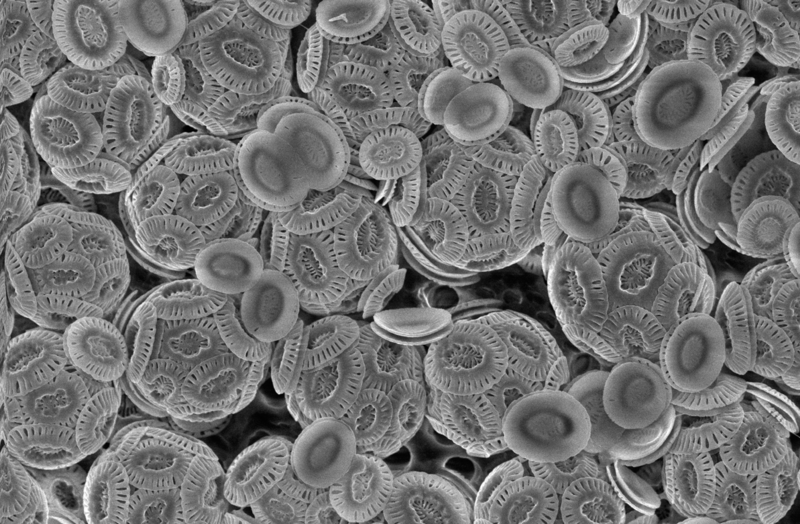

Coccolithophores

Appearance and Size

These are small phytoplankton, usually 5 to 20 micrometres, characterised by calcium carbonate plates that give them a chalky appearance.

Behaviour

Coccolithophores are photosynthetic and require stable, stratified water conditions. They play a role in reflecting solar radiation due to their calcium carbonate shells.

Reproduction Cycle

Coccolithophores undergo both asexual and sexual reproduction, forming resilient cysts to survive adverse conditions.

Habitat and Range

These organisms are primarily found at the edges of the Antarctic convergence, where water is warmer and more stable. They contribute to calcium carbonate cycling in the Southern Ocean, albeit in lower abundance than diatoms.

Dinoflagellates

Appearance and Size

Dinoflagellates have a distinctive armour of cellulose plates and two flagella for movement. They range from 15 to 40 micrometres.

Behaviour

Some dinoflagellates are mixotrophic, capable of both photosynthesis and predation on small particles. They exhibit bioluminescence as a defence mechanism and form cysts to survive harsh conditions.

Reproduction Cycle

They reproduce mostly by binary fission and form dormant cysts to withstand adverse environmental conditions.

Habitat and Range

These organisms are primarily found at the edges of the Antarctic convergence, where water is warmer and more stable. They contribute to calcium carbonate cycling in the Southern Ocean, albeit in lower abundance than diatoms.

Zooplankton

Zooplankton, the primary consumers, feed on phytoplankton and other organic material, making them vital in transferring energy to higher trophic levels. The dominant types of zooplankton in Antarctic waters include krill, copepods, and gelatinous organisms like salps and comb jellies.

Krill (Euphausia superba)

Appearance and Size

Krill are small crustaceans, generally between 35 and 55 millimetres in length, with a semi-transparent body and red-tinted eyes.

Behaviour

Krill form dense swarms, facilitating mass feeding by larger predators. They are vertical migrators, rising to surface waters to feed at night and descending to avoid predators during the day.

Reproduction Cycle

Krill have a multi-stage life cycle, with spawning timed to coincide with phytoplankton blooms, ensuring that young have ample food. Juveniles feed on phytoplankton within sea ice during winter.

Habitat and Range

Krill are widely distributed across the Southern Ocean, particularly in phytoplankton-rich areas like the Antarctic Peninsula, Ross Sea, and Weddell Sea. They rely on both open waters in summer and sea ice in winter.

Copepods

Appearance and Size

Copepods range from 0.5 to 5 millimetres in size, with an elongated body and long antennae.

Behaviour

They are filter feeders, capturing phytoplankton and organic particles, and many undergo vertical migration to optimise feeding and predator avoidance.

Reproduction Cycle

Many copepods enter a dormant phase during the winter, allowing them to conserve energy until the return of phytoplankton blooms in spring.

Habitat and Range

Copepods are found throughout Antarctic waters, from ice-covered to open ocean environments, with high densities in nutrient-rich areas.

Gelatinous Zooplankton (Salps and Comb Jellies)

Appearance and Size

Salps are barrel-shaped and gelatinous, ranging from a few millimetres to several centimetres, while comb jellies have a ciliated, jelly-like structure.

Behaviour

Salps are efficient filter feeders, consuming large volumes of water to extract phytoplankton, while comb jellies are predatory, feeding on smaller zooplankton.

Reproduction Cycle

Salps reproduce rapidly through both asexual and sexual reproduction, responding to phytoplankton availability with population booms.

Habitat and Range

Gelatinous zooplankton are widespread but highly variable in density, depending on phytoplankton concentrations. Salps sometimes directly compete with krill for food.

Ecological Roles and Interactions

The relationship between phytoplankton and zooplankton is fundamental to Antarctic ecosystems. Phytoplankton, thriving during the Antarctic summer, provides a food source for zooplankton populations. This seasonal bloom-bust cycle is crucial for sustaining the Southern Ocean’s high productivity, where zooplankton, especially krill, serve as the primary food source for higher trophic levels, including fish, birds, and mammals.

Zooplankton’s feeding behaviours and vertical migrations drive nutrient cycling within the Southern Ocean. As zooplankton graze on phytoplankton, they release nutrients through excretion, supporting new phytoplankton growth. The sinking of faecal pellets also facilitates carbon sequestration, a vital function in global carbon cycling as organic matter is transported to deeper ocean layers.

Krill are particularly important, as they link primary producers (phytoplankton) to a wide array of Antarctic predators, from penguins to baleen whales. They are considered a keystone species, with their abundance directly influencing the survival of many other species. During winter, krill’s adaptation to feed on phytoplankton embedded within sea ice ensures they can persist through the winter months when free-floating phytoplankton are scarce, stabilising their populations for the spring bloom.

The diversity of planktonic species highlights the complex ecological adaptations necessary for survival in Antarctic waters. Phytoplankton’s role as primary producers and zooplankton’s function as consumers create a dynamic foundation that supports a highly productive ecosystem. Krill, in particular, connect primary and secondary producers with apex predators, underscoring the intricate dependencies within the Antarctic marine environment and the ecological importance of plankton in supporting life in one of Earth’s most extreme ecosystems.