The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, spanning the late 19th to early 20th centuries, was characterized by a series of expeditions that sought to explore and understand the Antarctic continent.

The period was marked by remarkable feats of endurance, pioneering scientific research, and the quest for geographical discoveries, including attempts to reach the South Pole. It produced legendary figures whose names are synonymous with perseverance, leadership, and the spirit of exploration.

It’s also an age marked by patriotic drive, arrogance, the seeking of glory for self and country, and varying levels of ineptitude and arrogance, often resulting in disaster.

List of Expeditions

Click below to jump to each section

The Belgian Antarctic Expedition (1897–1899)

The Southern Cross Expedition (1898–1900)

The Discovery Expedition (1901–1904)

The Gauss Expedition (1901–1903)

The Swedish Antarctic Expedition (1901–1904)

The Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (1902–1904)

The Third French Antarctic Expedition (1903–1905)

The Nimrod Expedition (1907–1909)

The Fourth French Antarctic Expedition (1908–1910)

The Japanese Antarctic Expedition (1910–1912)

The Amundsen South Pole Expedition (1910–1912)

The British Antarctic Expedition (Terra Nova Expedition- 1910-1913)

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911–1914)

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition (1914–1917)

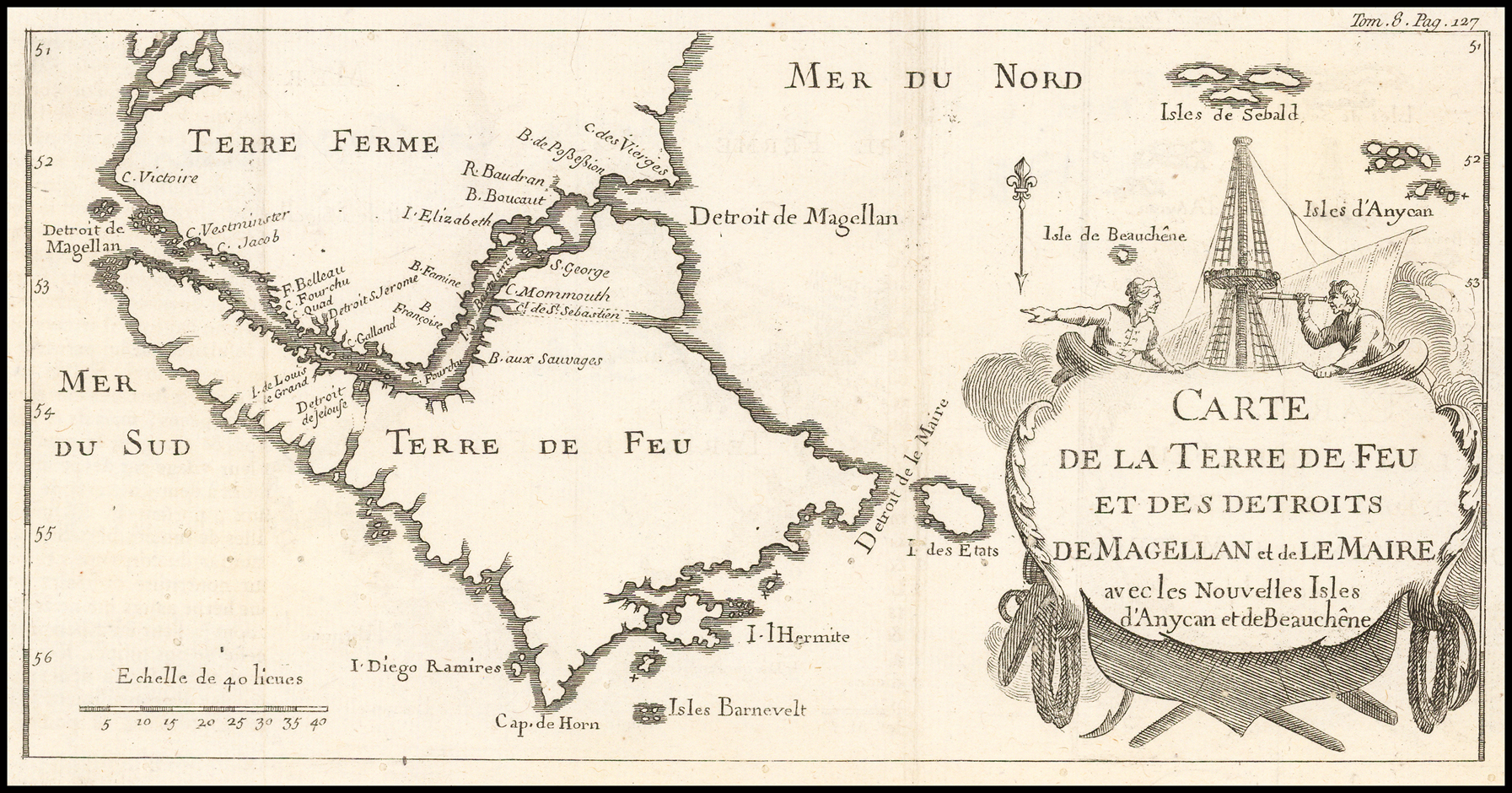

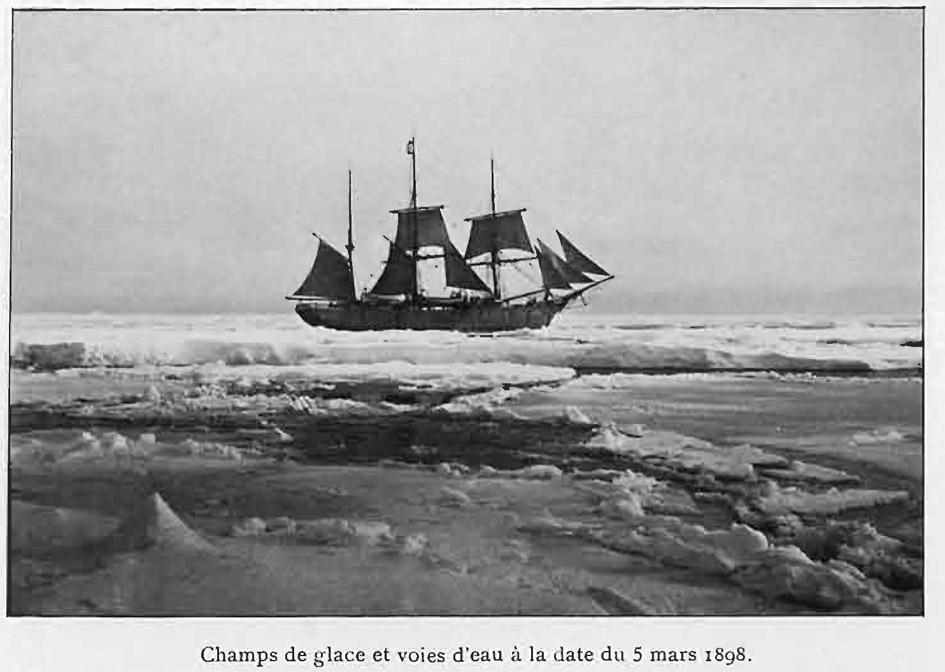

The Belgian Antarctic Expedition (1897–1899)

The Belgian Antarctic Expedition, led by Adrien de Gerlache between 1897 and 1899, marked a significant milestone in the history of Antarctic exploration. This expedition, aboard the ship Belgica, was the first to purposefully winter in the Antarctic, a feat that had not been attempted previously. Driven by scientific and exploratory ambitions, de Gerlache and his international crew of scientists and sailors ventured into unknown polar waters, facing severe challenges that tested their endurance and resilience.

The Belgica expedition contributed lasting achievements and discoveries, establishing Belgium as a pioneering force in the early exploration of Antarctica.

Ambitious Aims: Advancing Antarctic Science and Discovery

Adrien de Gerlache’s primary goal for the Belgian Antarctic Expedition was to conduct scientific research in Antarctica, following a wave of European interest in polar exploration. De Gerlache aimed to investigate Antarctica’s uncharted regions and make geographical discoveries that would contribute to the broader field of polar science. Recognising that systematic study in Antarctica had been limited, the expedition’s objectives included mapping unknown coastlines, documenting climatic conditions, and studying the Antarctic ecosystem. With scientists on board, including the renowned Frederick Cook and the young Roald Amundsen, the Belgica set sail from Antwerp in 1897, poised to enhance scientific understanding of the southern polar region.

This expedition was among the first to carry scientists specifically trained in meteorology, oceanography, and biology, equipped to gather data on Antarctic conditions. The crew’s diversity—Belgian, Norwegian, Polish, and American—demonstrated de Gerlache’s ambition to make this expedition a truly international scientific effort. This collaborative approach anticipated the later international character of Antarctic exploration and laid the groundwork for cooperative scientific study.

Severe Challenges in the Antarctic Winter

As the Belgica entered the icy waters of the Antarctic Peninsula, the expedition faced unprecedented challenges that underscored the extreme conditions of Antarctic exploration. In March 1898, while charting the Biscoe Islands and surrounding areas, the ship became trapped in pack ice, rendering escape impossible. De Gerlache and his crew were forced to endure the Antarctic winter—a scenario they had not initially intended or fully prepared for. This unplanned overwintering introduced a series of physical and psychological hardships that severely tested the crew’s resolve.

The crew faced extreme isolation, frigid temperatures, and nearly complete darkness as the Antarctic winter set in. The lack of sufficient food and fresh produce led to scurvy and other health complications, placing crew members at severe risk. The harsh conditions also had a profound psychological impact, with several crew members suffering from depression and other mental strains. Amidst these difficulties, Frederick Cook and Roald Amundsen applied resourceful measures, devising methods to alleviate scurvy and improve crew morale. Cook’s insistence on consuming fresh seal and penguin meat proved crucial in combating vitamin deficiencies, becoming a lesson in survival that influenced future polar expeditions.

Achievements and Contributions to Antarctic Science

Despite these extreme conditions, the Belgian Antarctic Expedition made substantial contributions to the scientific understanding of Antarctica. The expedition gathered the first systematic meteorological data from an Antarctic winter, recording temperatures, wind patterns, and atmospheric pressure, which provided valuable insights into the region’s climate. This data was essential for future Antarctic exploration, as it revealed the unique climatic characteristics of the Antarctic winter, including temperature extremes and prolonged darkness.

In addition to meteorological observations, the expedition documented geological formations, marine species, and Antarctic wildlife. The crew collected samples of flora and fauna, some of which were previously unknown to science, laying the groundwork for future biological studies in the Antarctic region. The expedition’s navigation and charting of the Antarctic Peninsula and surrounding islands added detail to existing maps, improving geographical knowledge and enhancing safety for subsequent voyages.

Historical Significance and Lasting Legacy

The Belgian Antarctic Expedition holds a unique place in the history of Antarctic exploration. By surviving the first overwintering in Antarctica, de Gerlache and his crew demonstrated the resilience required for extended polar missions. Their experiences highlighted the physiological and psychological challenges posed by the Antarctic environment, which would inform future explorers on how to better prepare for such extreme conditions. The successful return of the Belgica crew validated the feasibility of long-term scientific research in Antarctica, inspiring other nations to mount their own expeditions in the coming decades.

The expedition’s influence extended beyond the scientific data it gathered. The experiences of Cook and Amundsen on the Belgica were instrumental in shaping their future careers in polar exploration. Cook’s medical interventions and Amundsen’s resourcefulness were later evident in their respective achievements, with Amundsen eventually leading the first successful expedition to the South Pole in 1911. The Belgica expedition thus served as a formative experience for some of the 20th century’s most renowned polar explorers, demonstrating the expedition’s impact on the trajectory of Antarctic exploration.

In sum, the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–1899 stands as a landmark in early Antarctic exploration, achieving unprecedented insights into the continent’s climate, biology, and geography. De Gerlache’s venture into the unknown brought vital knowledge and inspired further international scientific exploration of Antarctica, positioning the expedition as a cornerstone in the history of polar exploration.

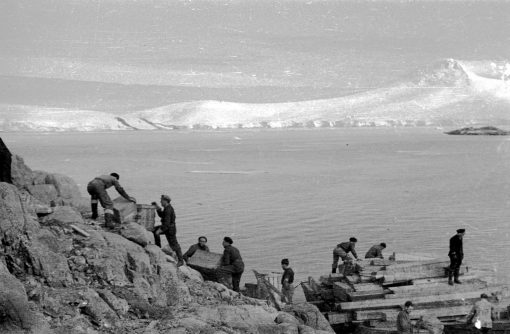

The Southern Cross Expedition (1898–1900): Foundations of Antarctic Fieldwork and Overwintering

The Southern Cross Expedition, officially known as the British Antarctic Expedition, marked a turning point in the early exploration of Antarctica. Funded by Anglo-Norwegian explorer Carsten Borchgrevink and supported by the British press magnate Sir George Newnes, this expedition was the first to intentionally overwinter on the Antarctic continent. With a strong focus on scientific research and pioneering fieldwork, the Southern Cross Expedition became one of the earliest to systematically study the Antarctic environment, paving the way for future expeditions in terms of both survival tactics and scientific contributions.

Bold Aims and Preparations for Extended Antarctic Exploration

The Southern Cross Expedition aimed to establish a British presence in Antarctica while conducting comprehensive scientific observations. Borchgrevink, who had previously ventured to Antarctica as part of a whaling expedition, sought to demonstrate that sustained research was possible in the extreme Antarctic environment. His goals included studying the region’s weather patterns, natural resources, and magnetic phenomena. The Southern Cross Expedition’s ambitious scope was inspired by the growing scientific interest in the polar regions, especially as nations began to see Antarctica as a frontier for exploration and discovery.

Borchgrevink’s team, consisting of scientists and experienced Norwegian sled drivers, was equipped with an impressive array of scientific instruments for meteorological, magnetic, and biological studies. The expedition’s vessel, the Southern Cross, was also outfitted to withstand the rigours of Antarctic ice and carry necessary supplies for overwintering. This preparation reflected Borchgrevink’s commitment to ensuring the success of his mission, making it one of the first expeditions to Antarctica with a structured and methodical approach to scientific investigation.

Overwintering at Cape Adare: Surviving the Antarctic Winter

In early 1899, Borchgrevink and his team landed at Cape Adare, making them the first group to intentionally overwinter on the Antarctic continent. This milestone in Antarctic exploration provided the team with a unique opportunity to study seasonal changes, though it also exposed them to severe isolation and extreme environmental conditions. The team constructed prefabricated huts, which offered basic shelter from the elements, although the limited insulation and confined space presented challenges during the long winter months.

The Cape Adare location, with its rocky shore and abundant wildlife, allowed the expedition to observe seals, penguins, and other Antarctic species throughout the year. However, winter conditions proved harsh. Strong katabatic winds and extreme cold confined the men to their shelters for extended periods, testing both their resilience and morale. Borchgrevink’s team successfully endured the winter, learning valuable survival strategies, including the importance of maintaining physical activity and social structure to combat the effects of isolation. These experiences became a reference point for later Antarctic expeditions that also needed to endure the polar night.

Scientific Achievements and Geographic Exploration

Despite the limitations imposed by the harsh environment, the Southern Cross Expedition achieved notable scientific accomplishments. The expedition’s meteorological studies provided the first continuous record of Antarctic weather conditions over an entire year, offering insights into temperature trends, wind speeds, and seasonal changes. This data contributed to the foundational understanding of the Antarctic climate, valuable for both scientific study and future expedition planning.

In addition to meteorological observations, the expedition conducted early biological and geological surveys. The team documented marine and terrestrial species, cataloguing numerous specimens and noting adaptations that enabled survival in the extreme cold. The observations of Adélie penguins and Weddell seals, which thrived at Cape Adare, added to the limited knowledge of Antarctic wildlife and supported future ecological studies.

Geographically, Borchgrevink’s expedition made significant advances by exploring the Ross Sea and reaching further south than previous expeditions. The team ventured inland, marking the first recorded human travel across the Antarctic ice cap and demonstrating that inland exploration was feasible, albeit challenging. By pushing inland from Cape Adare, Borchgrevink’s team opened the way for future expeditions to consider extensive inland exploration and travel.

Historical Significance and Legacy of the Southern Cross Expedition

The Southern Cross Expedition holds a crucial place in the history of Antarctic exploration. Borchgrevink’s success in overwintering on the continent demonstrated that humans could survive the Antarctic winter, which was a critical factor for future long-term scientific and exploratory missions. The meteorological and biological data collected during this overwintering period laid essential groundwork for the growing field of Antarctic science, while the experience gained in survival and logistics provided a model for subsequent expeditions.

Moreover, Borchgrevink’s expedition served as a precursor to the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. His international team and scientifically oriented approach set a precedent for later expeditions by Robert Falcon Scott, Ernest Shackleton, and Roald Amundsen. Borchgrevink’s achievements, including his inland travels, illustrated the continent’s potential for exploration beyond the coastal areas and inspired confidence that scientific knowledge could be gained despite the extreme conditions.

In conclusion, the Southern Cross Expedition from 1898 to 1900 stands as a pioneering venture that expanded the early exploration of Antarctica. By establishing the first overwintering base, conducting systematic scientific research, and achieving inland exploration, Borchgrevink’s team laid the foundation for future Antarctic expeditions. This early expedition remains a testament to the resilience and adaptability required in polar exploration, leaving a legacy that influenced the trajectory of Antarctic exploration for years to come.

The Discovery Expedition (1901–1904): Laying the Foundations of Modern Antarctic Science

The British National Antarctic Expedition, better known as the Discovery Expedition, led by Robert Falcon Scott from 1901 to 1904, was a landmark venture that combined ambitious scientific aims with exploration. Sponsored by the Royal Geographical Society and the British Admiralty, the expedition aimed to further the early exploration of Antarctica by studying its geography, biology, and geology.

Scott’s expedition became a pivotal moment in the history of Antarctic exploration, setting new standards in scientific research and establishing Britain as a central player in the polar sciences.

Scientific Goals: Uncovering Antarctica’s Secrets

The Discovery Expedition was launched with a dual focus on exploration and scientific discovery. Scott’s objectives included mapping uncharted territories, reaching high southern latitudes, and gathering extensive scientific data. The expedition aimed to address the pressing questions of the day: the structure of Antarctica’s ice sheets, the continent’s climate, and the nature of its flora and fauna. The scientific team, which included biologist Edward Wilson and geologist Hartley Ferrar, sought to conduct comprehensive studies in meteorology, magnetism, biology, and geology.

The expedition set sail on the specially built ship Discovery, designed to withstand ice and house a substantial team of scientists. The dedication to a rigorous scientific programme was unprecedented, making the Discovery Expedition one of the earliest ventures to systematically study Antarctica across multiple scientific disciplines. This focus on methodical scientific investigation reflected the transition from purely exploratory missions to research-oriented expeditions that would characterise modern Antarctic exploration.

Challenges in the Harsh Antarctic Environment

Upon reaching the Ross Sea in early 1902, the Discovery* became trapped in the pack ice near Ross Island, where Scott established a base for conducting research and launching exploratory journeys. The harsh Antarctic environment posed significant obstacles to both scientific study and survival. The expedition endured severe winters, with freezing temperatures, gale-force winds, and prolonged isolation, challenging the resilience of Scott’s team.

Sledging journeys presented another daunting challenge. In an effort to explore inland and reach higher latitudes, Scott led a sledge party southward, facing treacherous conditions and constant risks of frostbite, scurvy, and exhaustion. Despite these hardships, Scott’s team pushed to 82°17′ S, setting a record for the farthest south reached at the time. This achievement was a testament to their determination and marked a milestone in the early exploration of Antarctica, although the gruelling conditions foreshadowed the extreme difficulties of polar travel.

Major Discoveries and Scientific Achievements

The Discovery Expedition made significant strides in documenting the natural history, geology, and geography of Antarctica. Edward Wilson’s extensive studies on Antarctic wildlife, particularly on emperor and Adélie penguins, provided the first detailed accounts of these unique species. Observations of the breeding behaviour, diets, and adaptation strategies of Antarctic wildlife added a new dimension to the scientific understanding of polar ecosystems, creating a foundation for Antarctic biological studies.

Geologically, Hartley Ferrar conducted ground-breaking research on the rock formations around McMurdo Sound, confirming the volcanic nature of Ross Island. His studies also uncovered fossils, offering insights into Antarctica’s prehistoric environment and supporting theories that the continent was once part of the ancient supercontinent Gondwana. These findings had profound implications, reshaping scientific perceptions of Antarctica’s past and its connections to other continents.

The expedition also yielded valuable meteorological and magnetic data. Through systematic measurements, Scott’s team collected information on temperature fluctuations, wind patterns, and barometric pressure, which helped establish baselines for understanding Antarctic weather and its influence on global climate. Magnetic observations contributed to knowledge about the South Magnetic Pole, enhancing navigational data and aiding future expeditions in the region.

Historical Significance and Legacy of the Discovery Expedition

The Discovery Expedition left an enduring legacy, transforming the approach to Antarctic exploration and research. Unlike earlier expeditions, which often prioritised geographic discovery, Scott’s team achieved a balance between exploration and scientific inquiry, showing that both could coexist and mutually enrich each other. This shift inspired future Antarctic missions to place scientific research at the forefront of their objectives, a principle that continues to define Antarctic exploration today.

The expedition also had a lasting impact on polar leadership and training. Scott’s experience as leader of the Discovery prepared him for his later expedition to the South Pole, while his collaboration with scientists like Wilson influenced the professionalisation of polar research. The insights gained from the expedition on survival, logistics, and health management in extreme environments provided valuable lessons for later polar explorers, including Ernest Shackleton and Roald Amundsen.

The Discovery Expedition of 1901–1904 was a milestone in the early exploration of Antarctica, marking the transition from exploratory voyages to structured scientific expeditions. The expedition’s comprehensive research and pioneering spirit laid the groundwork for a century of Antarctic science, establishing a legacy of inquiry, resilience, and discovery that continues to shape our understanding of the continent today.

The Gauss Expedition (1901–1903): Germany’s Contribution to Antarctic Exploration and Science

The Gauss Expedition, officially known as the German Antarctic Expedition, was launched in 1901 under the leadership of geophysicist and polar scientist Erich von Drygalski. Sponsored by the German government, this expedition marked Germany’s first official venture into Antarctic exploration.

With a strong focus on scientific research, the Gauss Expedition aimed to expand the understanding of Antarctica’s geography, climate, and geology. Despite harsh conditions, the expedition achieved significant milestones in Antarctic science and set new standards for future German polar exploration.

Scientific Aims: A Comprehensive Study of Antarctica

The primary objective of the Gauss Expedition was to conduct a thorough scientific investigation of Antarctica, covering disciplines such as geology, meteorology, glaciology, and biology. Drygalski, a seasoned scientist with experience in Arctic research, sought to establish Germany as a leader in polar science. The expedition’s goals included mapping uncharted areas of the Antarctic coastline, studying the continent’s ice formations, and conducting systematic meteorological and geological observations.

To achieve these aims, the expedition was equipped with cutting-edge scientific instruments, reflecting Germany’s commitment to detailed and accurate data collection. Unlike previous expeditions focused on geographic discovery, the Gauss Expedition prioritised scientific inquiry, with a dedicated team of researchers on board. This approach highlighted Germany’s intent to advance Antarctic science, as the expedition intended to gather comprehensive data that would contribute to a broader understanding of Antarctica’s role in global systems.

Challenges of the Icy South and Ship Entrapment

In early 1902, after reaching the unexplored coast of East Antarctica, the Gauss—the expedition’s specially designed ship—became trapped in thick sea ice. This unanticipated entrapment forced the expedition to overwinter in the ice, a challenging situation that tested the resilience and adaptability of Drygalski and his crew. Despite repeated attempts to free the ship, the Gauss remained immobilised, effectively transforming it into a floating research station for nearly a year.

The expedition faced severe hardships during this extended overwintering period. Isolation, freezing temperatures, and limited provisions presented ongoing difficulties for the crew. Drygalski implemented a rigorous schedule of scientific activities to maintain morale and make productive use of the time spent trapped in the ice. This enforced overwintering period, though unplanned, allowed the team to conduct extended studies of Antarctic conditions across the changing seasons, providing insights that shorter expeditions could not achieve.

Scientific Achievements: Mapping New Lands and Studying Antarctic Ice

The Gauss Expedition made several landmark discoveries that advanced scientific knowledge of Antarctica. The expedition documented and mapped a previously unknown section of East Antarctica, which Drygalski named Kaiser Wilhelm II Land, and a notable volcanic peak he named Gaussberg, in honour of the mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss. These geographical findings expanded the known Antarctic coastline, contributing valuable information to global maps and laying the groundwork for future German expeditions in the region.

The expedition’s scientific programme was comprehensive and yielded substantial data across multiple fields. Meteorological records collected over the year provided valuable information on Antarctic weather patterns, wind speeds, and temperature fluctuations. The Gauss crew also gathered extensive glaciological data, studying ice thickness, structure, and movement, which contributed to early understanding of the continent’s ice systems and their dynamics. Observations on the formation and stability of sea ice added important insights into Antarctic climate, which would later inform climate studies in the polar regions.

Additionally, the expedition conducted biological surveys, cataloguing various Antarctic organisms and collecting specimens for study. Observations of marine life, including unique fish species and plankton, provided new information on Antarctic ecosystems, while studies of seabirds and seals added to the limited biological records of the time. These findings enriched the scientific community’s knowledge of the extreme adaptations of life in polar conditions.

Historical Significance and the Legacy of the Gauss Expedition

The Gauss Expedition holds a prominent place in the history of Antarctic exploration due to its scientific rigor and the breadth of data collected. The expedition’s commitment to scientific research over geographic conquest set it apart from contemporaneous missions and aligned with Germany’s emphasis on expanding scientific frontiers. Drygalski’s achievements in Antarctic geology, meteorology, and biology established Germany as a serious contributor to polar science and paved the way for later German explorations in both polar regions.

The expedition’s unplanned overwintering period became an enduring aspect of its legacy, as it demonstrated the resilience needed for extended Antarctic missions. The experience gained in managing crew welfare and conducting scientific activities under extreme conditions provided valuable lessons for future polar expeditions. The Gauss Expedition also left a legacy of accurate records and thorough documentation, influencing Antarctic science for decades. The published results from the expedition served as an essential reference for subsequent explorers and researchers.

In conclusion, the Gauss Expedition of 1901–1903 represents a foundational moment in the early exploration of Antarctica. Through its detailed mapping, comprehensive scientific studies, and perseverance in the face of harsh conditions, the expedition made lasting contributions to Antarctic knowledge and established Germany’s reputation in polar research. This pioneering mission left an enduring scientific legacy, setting a standard for the rigorous approach that would characterise Antarctic exploration in the 20th century.

The Swedish Antarctic Expedition (1901–1904): Scientific Discoveries and Survival in the Harsh Antarctic Landscape

Led by Swedish geologist Otto Nordenskjöld, the Swedish Antarctic Expedition of 1901–1904 was a groundbreaking endeavour in the early exploration of Antarctica. With a strong emphasis on scientific research, this expedition focused on studying Antarctica’s geology, biology, and climate.

Despite facing severe challenges and unforeseen dangers, the Swedish Antarctic Expedition achieved significant scientific breakthroughs and showcased human resilience in the face of extreme Antarctic conditions.

Scientific Objectives: A Quest to Uncover Antarctica’s Natural History

Otto Nordenskjöld, an accomplished geologist with extensive experience, initiated the Swedish Antarctic Expedition with the primary goal of expanding scientific understanding of Antarctica’s geology, meteorology, and biology. Nordenskjöld and his team sought to conduct thorough geological surveys, analyse Antarctic weather patterns, and document native plant and animal life. The Swedish government and various international scientific societies backed the mission, highlighting the expedition’s importance as part of the broader wave of polar research at the turn of the 20th century.

Equipped with scientific instruments and provisions, the team departed aboard the Antarctic, a vessel specially prepared to withstand Antarctic conditions. Nordenskjöld’s objective was to establish a research base on the Antarctic Peninsula, a region with promising geological features and diverse wildlife. This mission marked one of the earliest attempts by a European expedition to explore and conduct comprehensive scientific studies in the remote areas of the Antarctic continent.

The Challenges of Isolation and Stranded Crew

Upon arriving on the eastern side of the Antarctic Peninsula in early 1902, Nordenskjöld and a small team set up a base on Snow Hill Island, where they began their research. The remaining crew on the Antarctic, led by Captain Carl Anton Larsen, planned to resupply the base periodically. However, in February 1903, tragedy struck when the Antarctic became trapped in ice and was subsequently crushed, forcing the crew to abandon ship. The team, stranded on nearby Paulet Island, faced one of the most harrowing survival challenges in the history of Antarctic exploration.

The men were cut off from the Snow Hill base, where Nordenskjöld and his scientists had established themselves for the winter. For nearly two years, the isolated team at Snow Hill persevered through extreme weather, isolation, and limited provisions, adapting to their environment by building shelters and subsisting on local wildlife. Meanwhile, Captain Larsen’s crew endured a harsh winter on Paulet Island, surviving on penguins, seals, and limited supplies salvaged from the wreck of the Antarctic.

The ordeal reached a dramatic conclusion in November 1903, when the Argentine rescue vessel Uruguay, sent by the Argentine government after no word had been received from the expedition, successfully retrieved the expedition members. The rescue underscored the unpredictable and dangerous conditions of early Antarctic exploration and highlighted the critical importance of international cooperation in polar missions.

Scientific Achievements and Contributions to Antarctic Knowledge

Despite the physical and psychological toll of isolation, the Swedish Antarctic Expedition made remarkable scientific contributions. Nordenskjöld and his team conducted extensive geological surveys of the Antarctic Peninsula, collecting rock samples, studying glacial formations, and mapping previously uncharted regions. These studies yielded insights into the geological structure of the continent, including evidence that Antarctica had once been part of the supercontinent Gondwana, an idea that would become central to the theory of plate tectonics in later decades.

The team’s meteorological data, gathered throughout the winter months, provided valuable information on Antarctic climate patterns, wind speeds, and temperature variations. This data helped build a more comprehensive understanding of Antarctic weather, which was crucial for future expeditions. The biological observations were equally significant, as the team documented various Antarctic species, including Adélie penguins, seals, and krill, providing insight into the adaptability of these species to harsh polar environments.

The expedition’s scientific achievements were published in a series of detailed reports that advanced knowledge in geology, meteorology, and biology, setting a high standard for research in the polar sciences. Nordenskjöld’s findings were particularly influential in geological studies, as they expanded understanding of Antarctica’s ancient connections with other southern landmasses.

Legacy of Survival and Scientific Dedication

The Swedish Antarctic Expedition’s story of survival and scientific achievement left an indelible mark on the history of Antarctic exploration. Otto Nordenskjöld and his team’s resilience in the face of adversity demonstrated the psychological and physical fortitude required for extended Antarctic missions. The expedition’s success in both surviving extreme conditions and conducting significant scientific research highlighted the value of careful preparation and the adaptability needed in polar exploration.

Moreover, the expedition underscored the importance of international support in polar missions. Argentina’s rescue of the stranded team helped establish a foundation for international cooperation in Antarctic exploration, a principle that would later become central to the Antarctic Treaty System. This collaboration emphasised the collective responsibility of nations in the face of polar challenges and laid the groundwork for shared scientific missions in the Antarctic.

The Swedish Antarctic Expedition of 1901–1904 is remembered as a monumental achievement in the early exploration of Antarctica. By overcoming near-disastrous conditions and advancing knowledge in geology, meteorology, and biology, Nordenskjöld’s expedition made lasting contributions to polar science. The expedition’s success and resilience set a precedent for future Antarctic exploration, leaving a legacy of scientific dedication, international cooperation, and survival in one of the world’s most extreme environments.

The Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (1902–1904): Advancing Antarctic Science and Exploration

The Scottish National Antarctic Expedition, led by Dr. William Speirs Bruce from 1902 to 1904, marked Scotland’s significant contribution to early Antarctic exploration. Driven by a commitment to scientific research, Bruce’s expedition aimed to extend geographic and scientific knowledge of Antarctica, focusing on areas largely unexplored by other expeditions.

The journey, conducted aboard the ship Scotia, yielded remarkable scientific achievements and demonstrated the importance of systematic research in understanding the Antarctic environment. This expedition laid a strong foundation for later Antarctic studies, positioning Bruce and his team as pioneers in polar science.

Scientific Aims: Scotland’s Ambitious Contribution to Antarctic Research

The primary objectives of the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition were to map new territories, gather extensive scientific data, and document the unique climate, flora, and fauna of the Antarctic region. Unlike many expeditions of the time that balanced scientific goals with exploration, Bruce’s focus was purely scientific. He aimed to explore the Weddell Sea region, a largely uncharted area of Antarctica, with the goal of conducting comprehensive studies in meteorology, oceanography, biology, and geology.

The expedition’s ship, Scotia, was outfitted with advanced scientific equipment for detailed measurements and sample collection, including instruments for magnetic, meteorological, and oceanographic research. Bruce’s team of specialists was tasked with collecting data that would provide a deeper understanding of Antarctica’s ecosystem and climate, establishing the expedition’s reputation as one of the most scientifically rigorous of its time.

Overcoming Adversity in Uncharted Waters

After departing from Troon, Scotland, in 1902, the *Scotia* sailed south towards the Weddell Sea, navigating through treacherous, ice-filled waters. The harsh Antarctic environment tested the endurance and adaptability of Bruce’s crew, with freezing temperatures and pack ice posing continual threats. In March 1903, the Scotia became trapped in ice in the Weddell Sea, forcing the team to endure an overwintering period on Laurie Island, one of the South Orkney Islands. This unplanned stay allowed the expedition to establish a research station, which they named Omond House, enabling year-round scientific study in Antarctica.

Despite the isolation and harsh winter conditions, Bruce’s team used this period productively, setting up meteorological and magnetic observation posts and conducting daily scientific observations. The overwintering experience, though challenging, underscored the team’s resilience and provided valuable long-term data that contributed significantly to early Antarctic science.

Significant Discoveries and Contributions to Antarctic Science

The Scottish National Antarctic Expedition made numerous scientific breakthroughs that enhanced understanding of the Antarctic region. While based on Laurie Island, Bruce’s team conducted the first comprehensive meteorological and magnetic observations in the area, documenting seasonal weather patterns, wind speeds, and temperature variations. These findings offered critical insights into the Antarctic climate and added valuable data for future meteorological studies.

Geologically, the expedition mapped significant portions of the South Orkney Islands and the Weddell Sea coastline, expanding geographic knowledge of the region. The team discovered and documented new geographic features, contributing to more accurate mapping of Antarctic waters and establishing new navigation routes for future explorers. These achievements were instrumental in defining the largely uncharted Weddell Sea, helping to fill gaps in global understanding of Antarctica’s geography.

In the biological field, the expedition collected extensive samples of Antarctic flora and fauna, documenting numerous marine and terrestrial species. The team’s research on penguins, seals, and various fish species contributed to the understanding of polar ecosystems, while the study of microorganisms in ice and water samples provided early insight into the biological adaptability to extreme conditions. These biological records served as a foundation for later Antarctic ecological studies and underscored the unique biodiversity of the region.

Establishing Laurie Island as a Permanent Research Outpost

One of the lasting legacies of the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition was the establishment of a permanent meteorological station on Laurie Island. After conducting a successful overwintering programme at Omond House, Bruce arranged for the Argentine government to continue operating the station, thus creating the first permanent research outpost in Antarctica. Argentina’s stewardship of the station on Laurie Island, which continues today as the Orcadas Base, marked the beginning of international cooperation in Antarctic research and underscored the importance of sustained scientific observation in the polar regions.

This permanent outpost provided continuous meteorological and magnetic data, making Laurie Island one of the earliest centres for Antarctic climate research. By securing international support for the station, Bruce demonstrated the value of collaborative Antarctic exploration, establishing a model for shared scientific goals that would later become central to the Antarctic Treaty System.

The Expedition’s Legacy and Impact on Antarctic Exploration

The Scottish National Antarctic Expedition’s accomplishments had a profound impact on the field of Antarctic exploration, highlighting the significance of dedicated scientific inquiry. Bruce’s rigorous approach to research set new standards for Antarctic expeditions, prioritising systematic data collection over territorial conquest or competitive objectives. His contributions to Antarctic geography, meteorology, and biology helped position Scotland as an important player in early Antarctic science.

The expedition’s work on Laurie Island laid the groundwork for future Antarctic stations and international research collaborations. The partnership between Bruce and Argentina in establishing a permanent meteorological station marked an early example of multinational cooperation in Antarctic exploration, a concept that would shape the development of Antarctic research in the 20th century.

In conclusion, the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition from 1902 to 1904 was a landmark in early exploration of Antarctica, combining scientific precision with endurance and determination. Through extensive research and the establishment of Laurie Island as a continuous research outpost, Bruce and his team expanded knowledge of Antarctic ecosystems, climate, and geology. Their achievements underscored the importance of systematic study and international collaboration, leaving a legacy that influenced Antarctic exploration and research for generations.

The Third French Antarctic Expedition (1903–1905): Scientific Exploration and Geographic Discovery in Adélie Land

Led by renowned polar scientist Jean-Baptiste Charcot, the Third French Antarctic Expedition marked a significant chapter in the early exploration of Antarctica. Building on the achievements of earlier French efforts, Charcot’s expedition focused on detailed geographic mapping and scientific study of Adélie Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The expedition, conducted aboard the specially designed ship Français, succeeded in extending scientific understanding of Antarctica and showcased the potential for rigorous research in polar conditions.

Aims and Preparations: Charcot’s Scientific Vision for Antarctica

Jean-Baptiste Charcot launched the Third French Antarctic Expedition with a dual mission: to conduct scientific research and expand geographic knowledge of previously unexplored Antarctic regions. Charcot, an experienced scientist and navigator, aimed to map areas of Adélie Land and the western coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, where little systematic exploration had been conducted. Unlike other expeditions of the period, which often prioritised national prestige, Charcot’s goals were firmly rooted in scientific curiosity and a commitment to advancing polar knowledge.

The Français was equipped with a comprehensive array of scientific instruments to measure magnetic fields, record meteorological data, and collect biological and geological samples. Charcot’s dedication to the scientific quality of the expedition attracted an international team of scientists and specialists, reflecting his intention to produce substantial contributions to the polar sciences. The French government and private patrons supported Charcot’s venture, underscoring the expedition’s scientific importance and positioning it as a major effort in Antarctic exploration.

Navigating the Icy Waters and Overcoming Environmental Challenges

After departing from South America in early 1904, the Français faced challenging navigation in the icy waters off the coast of Adélie Land. The expedition encountered thick pack ice, low temperatures, and frequent snowstorms, conditions that severely tested Charcot’s crew and the endurance of their vessel. Charcot’s experience and careful planning enabled the team to manoeuvre through the dangerous sea ice, though the obstacles they encountered underscored the harsh realities of Antarctic exploration.

In 1904, the Français became trapped in pack ice for an extended period. Charcot and his crew were forced to overwinter aboard the ship, an ordeal that tested their adaptability and resourcefulness. While isolated in the ice, the team maintained a strict regimen of scientific observations, conducting daily weather recordings, astronomical observations, and biological studies. Charcot’s ability to maintain morale and a structured routine during this difficult period allowed the crew to continue their work despite the isolation and extreme cold.

Achievements in Mapping and Geographic Exploration

The expedition achieved significant geographic milestones by charting previously unknown sections of the Antarctic Peninsula and parts of Adélie Land. Charcot’s team meticulously mapped large areas of the Antarctic coastline, documenting key features such as mountains, glaciers, and coastal formations. His charts of the Antarctic Peninsula, based on both observational and instrumental data, corrected inaccuracies from earlier expeditions and added new geographic details that enriched global maps of Antarctica.

In recognition of his contributions, Charcot named several features in honour of his supporters and scientific colleagues. His detailed maps of the Antarctic Peninsula were among the most accurate of the time, providing future expeditions with valuable navigational resources and advancing geographic knowledge of the region. These maps also included some of the earliest precise depictions of bays, inlets, and islands along the peninsula’s western coast, contributing to safer routes for subsequent explorers.

Scientific Discoveries and Contributions to Antarctic Research

The scientific findings of the Third French Antarctic Expedition added substantial knowledge in multiple fields, including biology, geology, and meteorology. Charcot and his team gathered extensive meteorological data, documenting temperature patterns, wind speeds, and atmospheric pressure, all essential to understanding the harsh Antarctic climate. This data was vital for future research, as it offered a comprehensive view of seasonal weather variations in the region.

The biological research conducted during the expedition contributed to early studies of Antarctic wildlife. Charcot’s team documented various species, including seals, penguins, and krill, providing important insights into the behaviours and ecological adaptations of Antarctic fauna. These observations laid a foundation for further research into the unique polar ecosystem, illustrating the diversity of life capable of surviving in extreme conditions.

Geological studies were another highlight of the expedition’s achievements. Charcot’s team collected rock samples and studied glacial formations, shedding light on the geological history of Antarctica and its connection to other continents. These samples supported the theory that Antarctica had once been part of the ancient supercontinent Gondwana, an idea that would later be central to the understanding of continental drift and plate tectonics.

Influence on Future Antarctic Exploration and Research

The Third French Antarctic Expedition became a benchmark for scientific and geographical standards in polar exploration. Charcot’s emphasis on precision in mapping and rigorous data collection elevated the scientific quality of Antarctic expeditions, inspiring future explorers to adopt similarly meticulous methods. His work in Adélie Land and the Antarctic Peninsula encouraged greater interest in these regions, ultimately leading to further French expeditions under Charcot’s leadership and continued international exploration in the Antarctic.

The expedition’s approach to polar science influenced a generation of explorers, setting an example for integrating structured research into geographic exploration. Charcot’s leadership demonstrated the value of maintaining scientific discipline under harsh conditions, fostering a culture of resilience and curiosity that would become hallmarks of Antarctic research. By blending exploration with thorough scientific investigation, the Third French Antarctic Expedition significantly enhanced global understanding of Antarctica’s climate, geography, and ecosystem.

The Nimrod Expedition (1907–1909): Ernest Shackleton’s Bold Pursuit of Antarctic Achievement

The Nimrod Expedition, officially known as the British Antarctic Expedition, was led by Ernest Shackleton from 1907 to 1909. This ambitious journey aimed to push the boundaries of Antarctic exploration, both geographically and scientifically.

Through an intense focus on reaching new latitudes and conducting detailed scientific research, Shackleton and his team made significant contributions to Antarctic knowledge and inspired subsequent exploration efforts. Though they faced formidable challenges, the expedition achieved historic milestones, setting new standards in the pursuit of polar exploration.

Aims and Preparation: Reaching New Heights in Antarctic Exploration

Shackleton’s primary objectives for the Nimrod Expedition were to reach the South Pole and advance scientific understanding of Antarctica’s geology, biology, and meteorology. Inspired by his earlier experience with the Discovery Expedition, Shackleton was determined to build on his past knowledge and establish Britain’s prominence in polar exploration. Securing funding and support proved challenging, but Shackleton’s perseverance allowed him to gather resources and assemble a team of skilled scientists, surveyors, and experienced polar explorers.

The Nimrod, a ship originally built for Arctic whaling, was chosen and modified for the Antarctic journey. Shackleton’s careful planning included acquiring the best available equipment for sledging, scientific research, and survival in the harsh environment. His team also brought ponies and an early motorised vehicle to aid in overland travel, demonstrating Shackleton’s willingness to innovate and explore new methods for polar transport.

Overcoming Adversity in Harsh Conditions

The expedition began in earnest when the Nimrod reached Antarctica’s Ross Sea region in early 1908. Shackleton established a base at Cape Royds on Ross Island, a location chosen for its proximity to both the South Pole and the active volcanic landscape of Mount Erebus. From this base, Shackleton’s team planned a series of sledging journeys to meet their exploration and scientific objectives.

The challenges of navigating Antarctica’s icy terrain and severe weather soon became apparent. Shackleton led a polar party on a gruelling attempt to reach the South Pole, contending with freezing temperatures, high winds, and limited supplies. The journey stretched the physical limits of the team, who battled scurvy, frostbite, and exhaustion. Despite reaching a record latitude of 88°23′ S, only 97 nautical miles from the pole, Shackleton made the difficult decision to turn back, prioritising his team’s survival over the goal of reaching the pole.

Though the polar attempt fell short, the journey marked a remarkable achievement in polar endurance and navigational skill. Shackleton’s decision to return rather than risk his team’s lives highlighted his leadership qualities and his respect for the limits imposed by Antarctica’s extreme environment.

Scientific Achievements and Geographic Discoveries

The Nimrod Expedition contributed extensively to Antarctic science and geography. Shackleton’s team conducted the first ascent of Mount Erebus, Antarctica’s second-highest volcano, documenting its unique volcanic activity and collecting samples for geological study. This ascent provided critical insights into the volcanic structure and composition of Ross Island, contributing to the broader understanding of Antarctic geology.

In addition to volcanic studies, the expedition made substantial progress in mapping the surrounding area. Shackleton’s team surveyed the Beardmore Glacier, one of the largest glaciers in the world, which they used as a route to advance toward the South Pole. This marked the first discovery and documentation of the glacier, a major geographic feature that would later be used by future expeditions, including those of Robert Falcon Scott.

The Nimrod Expedition also contributed to biological and meteorological studies. The team documented Antarctic species, including seals, penguins, and various bird species, observing their adaptations to the polar environment. Meteorological records collected throughout the expedition offered new data on Antarctic climate patterns, wind speeds, and temperature variations, adding to the scientific understanding of Antarctica’s environmental conditions.

Influence on Future Polar Exploration

The Nimrod Expedition set a precedent in Antarctic exploration, combining ambitious geographic aims with rigorous scientific inquiry. Shackleton’s leadership, decision-making, and achievements in reaching new latitudes established him as one of the foremost polar explorers of his time. His achievements in mapping uncharted regions, studying unique geological features, and pushing further south than any expedition before him solidified the expedition’s importance in the history of Antarctic exploration.

The expedition’s success, despite not reaching the pole, inspired a new wave of polar explorers. Shackleton’s decision to prioritise safety over glory influenced the principles of future Antarctic missions, emphasising the importance of calculated risk-taking and crew welfare. His innovations in transport, particularly the use of ponies and motorised vehicles, contributed to ongoing debates about the best methods for traversing Antarctic terrain.

In addition, the Nimrod Expedition’s scientific contributions laid groundwork for subsequent studies in Antarctic geology, biology, and meteorology. The maps, records, and observations produced during the expedition became invaluable resources for later explorers, including Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen, who used Shackleton’s routes and findings as reference points for their own journeys.

In summary, the Nimrod Expedition of 1907–1909 marked a defining moment in the early exploration of Antarctica. Through Shackleton’s vision, the expedition advanced scientific knowledge, achieved unprecedented geographic milestones, and demonstrated the resilience required for Antarctic exploration. The expedition’s achievements, methods, and approach to polar exploration continue to resonate in the field of Antarctic studies, underscoring the enduring importance of Shackleton’s efforts in the pursuit of polar discovery.

The Fourth French Antarctic Expedition (1908–1910): Charting New Territory and Expanding Antarctic Science

Led by the accomplished polar scientist Jean-Baptiste Charcot, the Fourth French Antarctic Expedition of 1908–1910 focused on systematic exploration and scientific study of the western coast of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Building upon the achievements of his previous expedition, Charcot sought to further map uncharted Antarctic regions and deepen scientific understanding of the continent’s unique geology, climate, and ecosystem. With a well-prepared team and a dedicated vessel, this expedition contributed substantially to early Antarctic exploration, cementing Charcot’s reputation as a leading figure in polar science.

Mission Objectives: Mapping and Expanding Scientific Knowledge

The Fourth French Antarctic Expedition was launched with a clear set of objectives that combined geographic exploration with rigorous scientific investigation. Charcot’s primary aim was to continue the work he had begun on the Third French Antarctic Expedition by exploring and charting the western coastline of the Antarctic Peninsula, a region still largely unmapped at the time. His goals included accurately mapping new coastal areas, collecting geological and biological specimens, and conducting detailed meteorological observations.

The expedition ship, Pourquoi-Pas?, was specially designed to withstand Antarctic ice and equipped with advanced scientific instruments. Charcot’s approach prioritised systematic research, with a team of geologists, meteorologists, biologists, and cartographers, all focused on gathering reliable data. This focus reflected Charcot’s dedication to advancing scientific understanding rather than claiming territory, setting his expedition apart in an era marked by nationalistic competition in polar exploration.

Navigating the Antarctic Peninsula’s Icy Waters

Upon reaching the Antarctic Peninsula in 1909, Charcot and his team faced significant challenges navigating the ice-laden waters. Thick pack ice, unpredictable weather, and strong winds posed continual threats to the Pourquoi-Pas?, requiring careful navigation and constant vigilance from the crew. Charcot’s experience and detailed planning enabled the team to work efficiently despite the difficult conditions, allowing them to maximise their time in the region.

Over the course of two seasons, the expedition undertook a series of coastal surveys and inland journeys, documenting previously uncharted territories and geological formations. The persistence and adaptability of Charcot’s team allowed them to complete extensive surveys even in the face of challenging Antarctic weather, marking a milestone in the systematic mapping of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Geographic Discoveries and Detailed Mapping Efforts

One of the most significant achievements of the Fourth French Antarctic Expedition was its detailed mapping of the western Antarctic Peninsula’s coastline. Charcot’s team documented numerous geographic features, including islands, glaciers, and bays, many of which were previously unknown to the scientific community. Notable discoveries included Marguerite Bay and several surrounding islands, features that would become reference points for future Antarctic expeditions. Charcot named many of these newly charted areas after prominent figures in science and geography, honouring the contributions of his peers to polar exploration.

The expedition’s charts and maps of the region were among the most accurate of their time, improving navigational safety for future explorers and providing a solid foundation for later mapping efforts. Charcot’s meticulous documentation of these features helped standardise the geographic knowledge of the Antarctic Peninsula, establishing an essential reference for subsequent expeditions.

Scientific Contributions: Advancing Knowledge in Geology, Biology, and Meteorology

The Fourth French Antarctic Expedition’s scientific accomplishments extended beyond geographic discoveries. Charcot’s team conducted thorough geological surveys, collecting rock samples and studying the region’s glacial formations. These studies provided insights into the Antarctic Peninsula’s geological history, supporting theories that Antarctica was once connected to other southern landmasses as part of the ancient supercontinent Gondwana. The team’s findings helped expand scientific understanding of Antarctic tectonics and glacial evolution.

In the field of biology, the expedition documented various Antarctic species, including penguins, seals, and fish, adding to the limited knowledge of life in the extreme polar environment. The team’s collection of biological specimens contributed to understanding how species adapted to harsh Antarctic conditions, laying groundwork for future ecological studies in the region.

Meteorological data collected by the expedition furthered knowledge of Antarctic climate patterns. The team recorded temperature fluctuations, wind speeds, and atmospheric conditions, providing valuable data on the unique weather patterns of the Antarctic Peninsula. This data helped fill gaps in the scientific community’s understanding of polar climate systems and was later used to inform broader studies on global climate.

Impact on Antarctic Exploration and Scientific Research

The Fourth French Antarctic Expedition of 1908–1910 made lasting contributions to Antarctic exploration and scientific research. Charcot’s commitment to rigorous data collection and precise mapping set a high standard for future expeditions, particularly in terms of systematic scientific study. His focus on detailed geographic documentation helped expand European knowledge of the Antarctic Peninsula and established a strong foundation for international Antarctic research in the years to come.

The expedition’s success demonstrated the value of combining exploration with focused scientific inquiry. Charcot’s methods influenced subsequent Antarctic missions, which increasingly adopted his approach of integrating fieldwork with scientific objectives. His achievements also fostered a deeper understanding of Antarctica as a unique environment worthy of dedicated study, shifting perceptions of the continent from a remote, inhospitable wilderness to a region of scientific and ecological significance.

In conclusion, the Fourth French Antarctic Expedition of 1908–1910 was a remarkable example of early Antarctic exploration that prioritised science and geographic precision. Through extensive mapping, geological study, biological research, and meteorological observation, Charcot and his team significantly advanced the global understanding of Antarctica. Their work provided critical insights into the continent’s geography and climate, establishing benchmarks in Antarctic research that continue to inform modern polar science.

The Japanese Antarctic Expedition (1910–1912): Japan’s Historic Venture into Antarctic Exploration

The Japanese Antarctic Expedition, led by Lieutenant Nobu Shirase, marked Japan’s first foray into Antarctic exploration. The expedition aimed to assert Japan’s presence in the emerging field of polar research, as well as to make geographic discoveries and gather scientific data about the Antarctic environment.

Despite limited resources and a late start in the polar season, Shirase and his team persevered through challenging conditions, contributing to early Antarctic exploration and establishing Japan as an active participant in the polar sciences.

Objectives and Motivation: Japan’s Bold Entry into Antarctic Exploration

Under the leadership of Nobu Shirase, the Japanese Antarctic Expedition was organised with the goals of exploring uncharted areas of Antarctica, conducting scientific observations, and establishing Japan’s position in polar research. Inspired by the recent achievements of European explorers such as Ernest Shackleton and Robert Falcon Scott, Japan sought to demonstrate its capabilities and scientific commitment on the global stage. Shirase, a former army officer with a keen interest in exploration, envisioned the expedition as an opportunity to contribute to the growing body of knowledge about the Antarctic continent.

The expedition’s funding came from private donations and limited government support, as Japan lacked a tradition of polar exploration. Despite financial constraints, Shirase managed to assemble a crew of experienced sailors and scientists. Their vessel, the Kainan Maru, was equipped with basic supplies and scientific instruments, although the expedition faced significant logistical challenges compared to its European counterparts.

Overcoming Logistical and Environmental Challenges

The Kainan Maru departed Tokyo in late 1910, arriving in Sydney in early 1911 to resupply before attempting the journey south. Due to delays and funding issues, the team arrived in Antarctica later than planned, complicating their efforts to establish a base and carry out their research. In early 1911, after a failed attempt to land on the Antarctic coast due to heavy pack ice, Shirase decided to winter in Australia, returning to Antarctica the following season with renewed determination.

In early 1912, Shirase and his team made their second attempt to land on the Antarctic continent. After navigating treacherous ice fields and enduring harsh weather, the Kainan Maru reached the eastern edge of the Ross Ice Shelf. Shirase led a small landing party that set up camp on the ice, enduring the intense cold to conduct exploratory work. The team pushed southward, advancing over the ice and reaching a latitude of 80°05′ S, a significant accomplishment given the limited resources and equipment at their disposal. Though unable to achieve their initial goal of reaching the South Pole, their progress represented a remarkable achievement for an expedition that had started with considerable disadvantages.

Geographic Discoveries and Scientific Observations

Despite its challenging conditions, the Japanese Antarctic Expedition made notable geographic and scientific contributions. Shirase’s team mapped portions of the Ross Ice Shelf and nearby coastal areas, recording observations of the landscape and ice formations. They documented the unique features of the terrain, including icebergs and crevasses, providing early geographic information about this remote area. These observations helped expand the global understanding of the Antarctic ice shelf system.

The expedition also conducted meteorological observations, gathering data on temperature, wind speeds, and atmospheric pressure. These records, while limited due to time constraints, contributed valuable information to the emerging knowledge of Antarctic climate conditions. The expedition’s scientific focus, though less extensive than other contemporary missions, reflected Japan’s commitment to serious study of the polar environment and demonstrated the country’s capability to conduct fieldwork in harsh polar conditions.

The Expedition’s Impact on Japanese and Global Antarctic Exploration

The Japanese Antarctic Expedition, though modest in scale, marked an important step for Japan in establishing itself as a nation committed to Antarctic exploration. Shirase’s determination and leadership, along with his team’s resilience in the face of extreme adversity, demonstrated Japan’s potential as a contributor to international polar research. Their expedition symbolised Japan’s entry into the field of Antarctic science, inspiring later Japanese expeditions and fostering national interest in polar studies.

On a global level, the expedition broadened the scope of international participation in Antarctic exploration, showing that countries outside Europe and North America could play a role in the polar sciences. While Shirase’s journey received mixed recognition at the time, it is now acknowledged as a significant achievement that expanded the diversity of perspectives in Antarctic research. The expedition contributed to a spirit of international cooperation and exploration that has continued to define Antarctic research in the modern era.

In summary, the Japanese Antarctic Expedition of 1910–1912 represents a landmark in the history of early Antarctic exploration. Through geographic discoveries, scientific observations, and sheer perseverance, Shirase and his team made an enduring impact on the field of polar research. Their expedition opened the door for Japan’s involvement in Antarctic science and underscored the potential for diverse international collaboration in exploring and understanding the Antarctic continent.

The Amundsen South Pole Expedition (1910–1912): Conquering the South Pole through Precision and Perseverance

The Amundsen South Pole Expedition, officially known as the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition, remains one of the most remarkable achievements in the early exploration of Antarctica. Led by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, the expedition aimed to reach the South Pole, a goal that had eluded all previous explorers.

Amundsen’s meticulous planning, use of innovative techniques, and exceptional leadership allowed his team to achieve the first successful journey to the South Pole, solidifying their place in the annals of polar exploration.

Mission Goals: The Drive to Reach the South Pole First

Roald Amundsen initially planned an expedition to the North Pole, but upon learning that Robert Peary had already claimed it, he redirected his focus to Antarctica. Amundsen’s new aim was to be the first to reach the South Pole, a feat that had become a highly coveted achievement in the field of Antarctic exploration. This goal placed him in direct competition with the British Terra Nova Expedition, led by Robert Falcon Scott, who was also attempting to reach the Pole.

Amundsen kept his South Pole intentions secret until shortly before departure, recognising the fierce competition for polar firsts and seeking to gain an advantage. With a strong team of seasoned polar explorers and skiers, Amundsen meticulously planned his route from the Bay of Whales along the Ross Ice Shelf to the high plateau of the Antarctic interior. His strategy involved setting up supply depots, carefully calculating distances, and employing efficient methods of travel, reflecting his commitment to a well-organised and effective mission.

Overcoming Environmental and Logistical Challenges

The Amundsen Expedition faced numerous challenges in the harsh Antarctic environment, including extreme cold, unpredictable weather, and difficult terrain. Amundsen’s decision to land at the Bay of Whales, an area closer to the Pole than other known access points, allowed the team a strategic starting point but also exposed them to hazardous ice conditions along the Ross Ice Shelf.

To counter these environmental challenges, Amundsen relied on a well-thought-out logistical plan. His team used sled dogs extensively, which proved faster and more reliable than ponies or motorised vehicles used by other expeditions. The choice of dogs allowed Amundsen to move efficiently, while the team’s skill in skiing and sledging further enhanced their mobility. Amundsen’s innovative use of furs, specially designed clothing, and lightweight equipment helped his men adapt to the extreme cold, preventing frostbite and maintaining morale. These methods showcased Amundsen’s understanding of polar conditions and his ability to innovate under challenging circumstances.

Reaching the South Pole: A Historic First in Antarctic Exploration

On December 14, 1911, after a gruelling 1,400-kilometre journey from their base at Framheim, Amundsen and his four-man team became the first humans to reach the South Pole. They raised the Norwegian flag, marking an historic achievement in the early exploration of Antarctica. Amundsen’s success in reaching the Pole was a result of his meticulous planning, as well as his team’s discipline and physical endurance.

Amundsen’s team spent three days at the Pole, gathering geographic and scientific data to confirm their achievement and mark their location precisely. They recorded observations on altitude, temperature, and atmospheric pressure, collecting valuable information about the conditions of the Antarctic interior. This data was essential not only to verify their position but also contributed to the emerging body of scientific knowledge about the South Pole region.

The return journey was equally demanding, but Amundsen’s careful planning of supply depots and reliance on dogs allowed the team to make the journey back safely and efficiently. By January 25, 1912, they returned to Framheim, having accomplished their mission with no loss of life, a remarkable feat given the era’s limited resources and the extreme conditions they faced.

The Expedition’s Impact on Antarctic Exploration

The Amundsen South Pole Expedition had a profound impact on Antarctic exploration, setting new standards for preparation, efficiency, and adaptation to polar environments. Amundsen’s use of sled dogs, precise planning, and lightweight equipment established a model of polar travel that would influence future expeditions. His reliance on tried-and-tested methods and emphasis on adaptability highlighted the importance of thorough preparation in extreme exploration.

Amundsen’s achievement at the South Pole also marked a significant point in the international race for Antarctic primacy. His success underscored Norway’s capabilities in polar exploration, bolstering its reputation as a leading nation in the field. The expedition’s scientific data, though secondary to the primary goal of reaching the Pole, contributed valuable information about the Antarctic interior. This included geographical coordinates, temperature readings, and atmospheric conditions at high altitudes. These contributions added to the early scientific understanding of Antarctica’s central regions, fostering a deeper interest in the continent’s role in global science.

Lasting Influence on Antarctic Exploration

While Amundsen’s triumph in reaching the South Pole is widely celebrated, his expedition’s influence extended beyond the initial achievement. The lessons learned from his approach to preparation, risk management, and teamwork became guiding principles for polar explorers and scientists alike, providing essential insights into the demands of Antarctic exploration.

In conclusion, the Amundsen South Pole Expedition of 1910–1912 stands as a monumental accomplishment in early Antarctic exploration. By reaching the South Pole first, Amundsen and his team made history, demonstrating unparalleled skill and discipline in one of the world’s harshest environments. Their success reshaped polar exploration, introducing new methods and inspiring future expeditions to Antarctica with its emphasis on preparation, precision, and resilience.

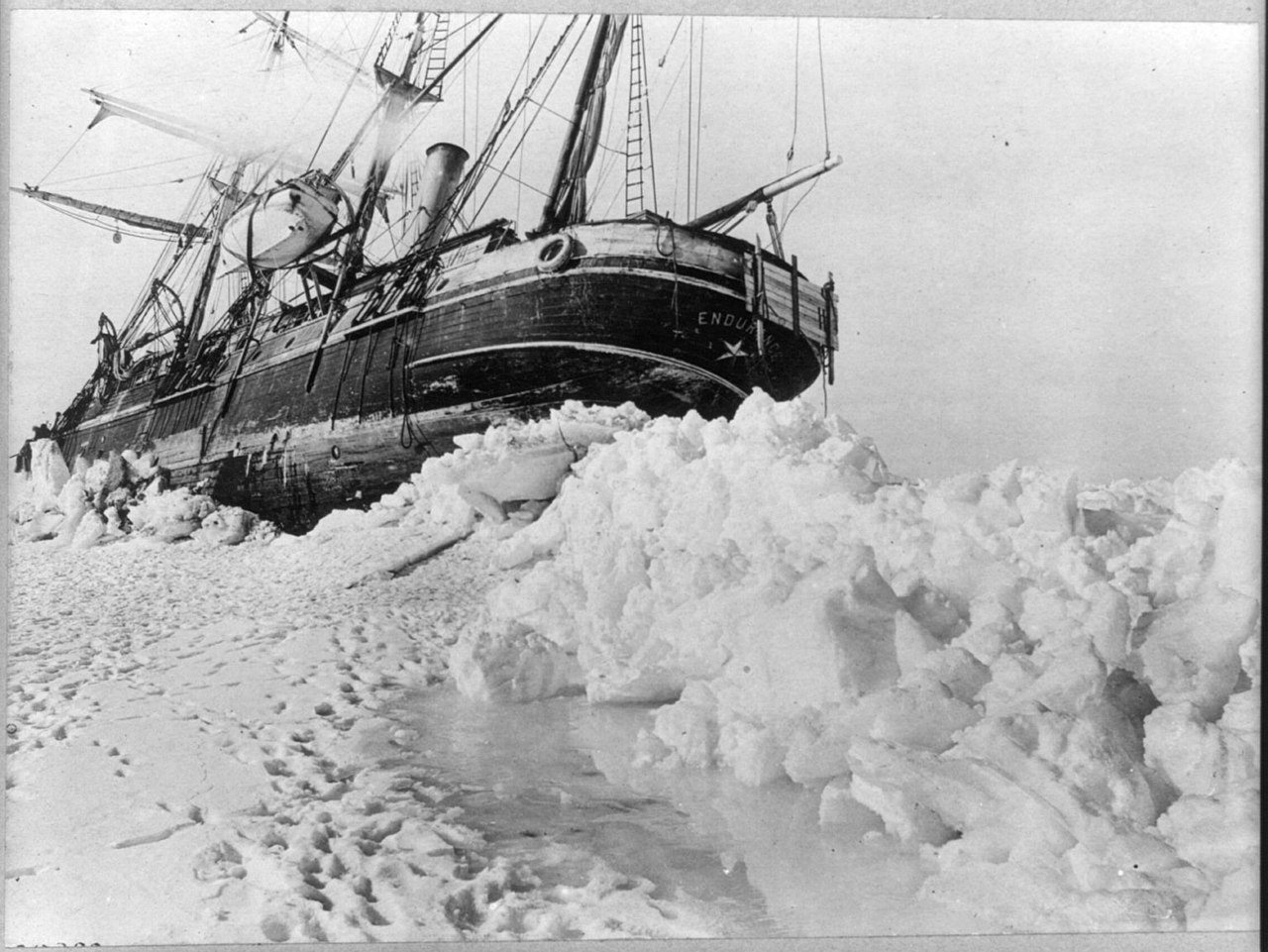

The Terra Nova Expedition (1910–1913): Tragedy, Scientific Discovery, and the Pursuit of the South Pole

The Terra Nova Expedition, officially known as the British Antarctic Expedition, was led by Robert Falcon Scott with the dual aim of reaching the South Pole and advancing scientific research in Antarctica. Although remembered for the tragic loss of Scott and his polar party, the expedition also made substantial contributions to Antarctic science, establishing a lasting legacy in early exploration of Antarctica.

Despite formidable challenges, the team achieved important scientific milestones, leaving behind data and discoveries that would prove invaluable to future Antarctic research.

Ambitions and Preparations: Aiming for the Pole and Advancing Science

Robert Falcon Scott launched the Terra Nova Expedition with a clear twofold objective: to be the first to reach the South Pole and to conduct extensive scientific research across a range of disciplines, including geology, biology, and meteorology. Scott’s vision extended beyond mere conquest; he sought to enrich Britain’s scientific understanding of Antarctica’s environment, geology, and ecosystems. The British Admiralty and Royal Geographical Society supported the mission, providing substantial funding and resources.

Scott selected the Terra Nova, a former whaling vessel, to transport the expedition. The team included skilled scientists and polar veterans, each equipped to contribute to the expedition’s scientific goals. In addition to sled dogs and ponies, Scott brought a pioneering motorised sledging system, aiming to test new methods of travel on the ice. His extensive preparations reflected his determination to ensure the expedition’s success, but the blend of traditional and unproven techniques created logistical challenges that would impact the journey.

Facing Extreme Conditions and Overcoming Hardships

Upon landing in Antarctica’s Ross Sea region, Scott’s team established their primary base at Cape Evans on Ross Island in January 1911. From this base, they conducted preliminary scientific studies and made preparations for the polar journey. Conditions on the continent proved harsher than anticipated, with unpredictable weather, snow-covered terrain, and shifting ice creating difficulties from the outset.

Scott began his polar journey in late 1911, leading a sledging team over the challenging terrain of the Ross Ice Shelf, through the steep and crevassed Beardmore Glacier, and onto the high polar plateau. The combination of cold temperatures, high winds, and physical exhaustion slowed their progress. As the team advanced, they faced continuous struggles with limited rations, frostbite, and the debilitating effects of scurvy. The ponies and motorised sledges proved unreliable in the extreme cold, forcing the team to rely heavily on man-hauling, which drained their energy and reduced their speed.

Despite these setbacks, Scott’s team reached the South Pole on January 17, 1912, only to find that Roald Amundsen’s Norwegian team had arrived five weeks earlier. The discovery of Amundsen’s flag at the Pole was a devastating blow to Scott and his team, who had endured months of hardship to achieve this goal.

Scientific Discoveries and Contributions to Polar Knowledge

Although the Terra Nova Expedition is often remembered for its tragic outcome, the team achieved significant scientific milestones, greatly expanding knowledge of the Antarctic continent. During their time at Cape Evans, the scientific staff conducted extensive studies, collecting valuable data on Antarctic geology, glaciology, biology, and meteorology. The expedition’s findings enriched understanding of the Antarctic landscape, as well as its unique flora and fauna.

Geologist Thomas Griffith Taylor and his team explored the Dry Valleys and discovered fossils, providing early evidence that Antarctica was once part of the ancient supercontinent Gondwana. This discovery would later support theories of continental drift and plate tectonics, shaping the field of Earth sciences. The expedition also conducted biological surveys of penguin colonies, seals, and marine organisms, documenting species adapted to Antarctica’s extreme environment and laying the groundwork for future ecological research.

Meteorological observations gathered throughout the expedition offered important insights into Antarctic weather patterns, including temperature fluctuations, wind speeds, and atmospheric conditions. These records would prove valuable in understanding the Antarctic climate and its influence on global weather systems. The Terra Nova Expedition’s data collection exemplified the intersection of exploration and scientific inquiry, establishing standards that would guide future Antarctic research.

The Return Journey and the Loss of Scott’s Polar Party

The return journey from the South Pole proved fatal for Scott and his four-man polar team, as they faced worsening weather and dwindling supplies. Exhausted and weakened, the party struggled against severe blizzards, and temperatures plummeted as they traversed the polar plateau. Each day’s progress slowed under the weight of physical and mental strain.

By March 1912, the situation had become dire. Team members Edgar Evans and Lawrence Oates perished along the way, with Oates famously leaving the tent in a final act of sacrifice to give his companions a greater chance of survival. The remaining three men—Scott, Edward Wilson, and Henry Bowers—ultimately succumbed to the harsh conditions, trapped by a blizzard only 11 miles from a supply depot. Scott’s final diary entries, found alongside the bodies months later, poignantly documented the team’s endurance and acceptance of their fate.

Enduring Impact on Antarctic Exploration and Science

The Terra Nova Expedition’s story captured the public’s imagination, cementing Robert Falcon Scott’s place in history as a symbol of courage and determination in the face of insurmountable odds. Despite the tragedy, the expedition’s scientific achievements were considerable and added greatly to the field of Antarctic research. The extensive data, specimens, and observations collected by the team contributed significantly to early Antarctic exploration, offering insights that would inform future expeditions and scientific study.

The expedition’s combination of geographic exploration and scientific dedication set a precedent for integrating research into polar missions. The work of the Terra Nova scientists in fields such as geology, biology, and meteorology demonstrated the importance of studying Antarctica beyond mere geographic conquest, promoting a view of the continent as a site for long-term scientific discovery. Scott’s expedition inspired later explorers to approach Antarctic exploration with similar rigour and curiosity, influencing generations of scientists and adventurers.