Early Exploration of Antarctica

Belief in the existence of a Southern landmass

Early exploration of Antarctica was driven by the widespread belief of a vast southern continent, known as Terra Australis. This idea was prevalent among geographers and explorers for centuries. This theoretical landmass was thought to exist in the southern hemisphere, balancing the known land masses of the northern hemisphere.

The earliest recorded mention of such a continent dates back to ancient Greek philosophers. Aristotle, in the 4th century BCE, postulated a large landmass in the south, which he believed was necessary to balance the continents in the north for the Earth to remain in equilibrium. This idea was further developed by Ptolemy, a Greco-Roman scholar of the 2nd century CE, who depicted Terra Australis on his world maps, although it was entirely speculative and not based on any direct observation or exploration.

Were the Polynesians the first to find Antarctica?

While European knowledge of Antarctica stemmed from theory, Polynesian oral traditions hint at far earlier encounters. Stories passed down speak of Ui-te-Rangiora, a Rarotongan explorer who sailed south to a frozen region, and Tamarereti, another Polynesian, who glimpsed the icy south. These traditions, though unverified, offer a fascinating glimpse into possible pre-European contact.

The Age of Exploration

The Age of Exploration, spanning the 15th to the 17th centuries, was a period marked by global maritime exploration, initiated by major European sea powers, particularly Portugal and Spain. This era was characterized by the search for new trading routes and territories, driven by economic, religious, and geopolitical motives. The exploration of the southern hemisphere, including speculative voyages towards Antarctica, was part of this broader context of discovery and paved the way for later exploration of Antarctica.

Click below to jump to each section:

- Ferdinand Magellan’s Voyage (1599-1522)

- Sir Francis Drake’s Circumnavigation (1577–1580)

- Dutch Exploration of the Southern Ocean: (1599–1643)

- Captain James Cook’s First Voyage (1768–1771)

- Captain James Cook’s Second Voyage (1772–1775)

- First Confirmed Sightings of the Antarctic Continent (1820–1821)

- Further Exploration and Mapping of Antarctica (1839–1893)

Magellan’s Voyage Across the Strait of Magellan (1519–1522)

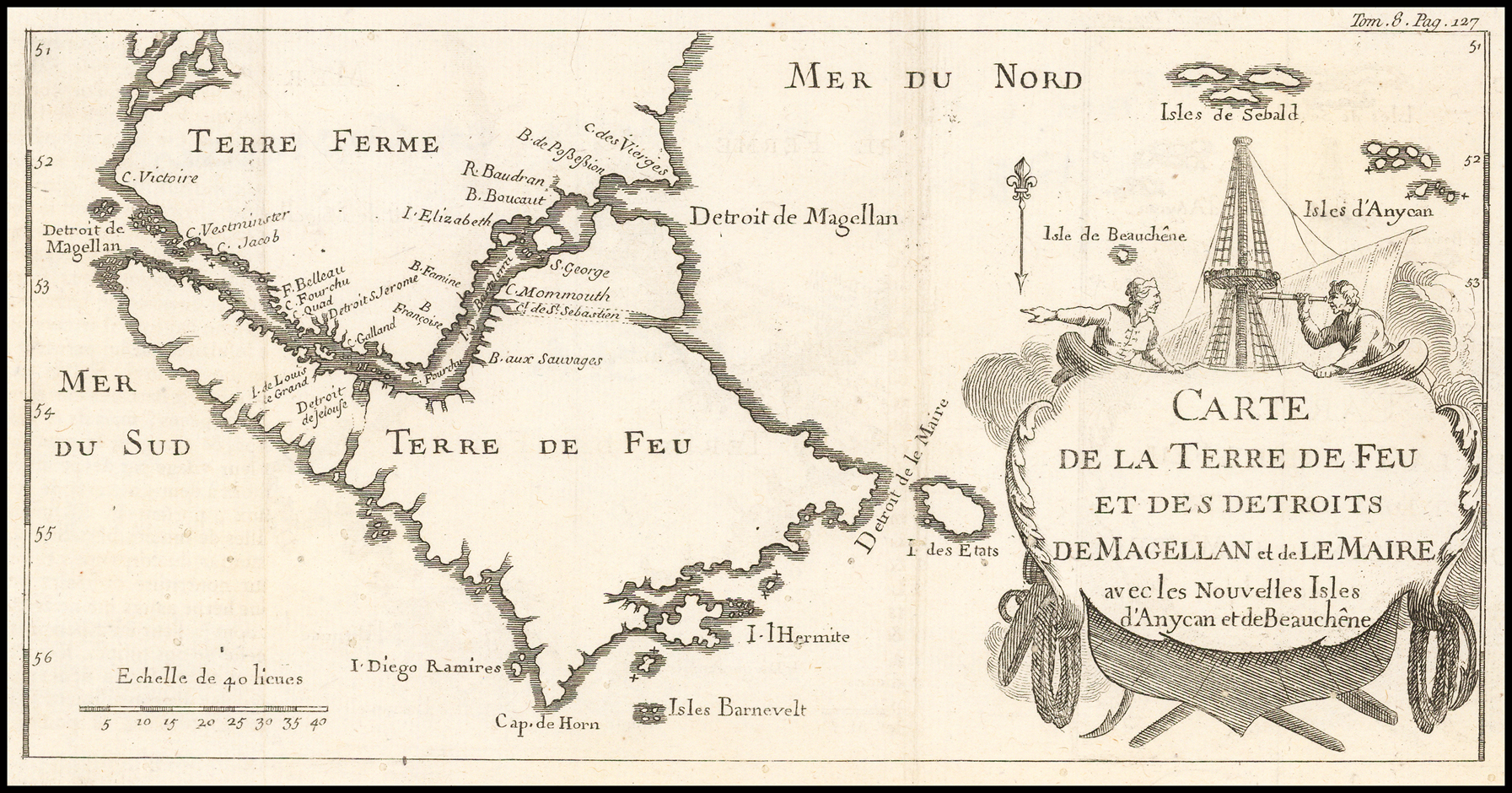

The early exploration of Antarctica and the southern oceans can be traced to the era of European maritime expansion, beginning with Ferdinand Magellan’s pioneering voyage. Magellan’s circumnavigation (1519–1522), initially backed by Spain, aimed to reach the Spice Islands (the Moluccas) by finding a western route, avoiding Portuguese-controlled waters.

His journey resulted in the discovery of a crucial passage, later named the Strait of Magellan, a key milestone in the early exploration of the southern hemisphere and a precursor to later Antarctic exploration.

Aim of the Expedition and the Discovery of the Strait

Magellan’s expedition, commissioned by the Spanish Crown, sought an alternative route to the lucrative Spice Islands by circumventing Portuguese territorial waters. As part of his route, Magellan sought to navigate southward to reach a passage through the Americas, hypothesising the existence of such a channel based on early accounts from explorers and navigators.

In October 1520, after a treacherous journey down the eastern coast of South America, the expedition found a passage near the 52nd parallel south, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. This strait, marked by complex geography with narrow waterways, unpredictable winds, and swift currents, became a crucial maritime discovery.

The discovery of the Strait of Magellan was momentous, as it offered a viable, albeit challenging, route to the Pacific and the Spice Islands without traversing Portuguese waters or the Cape of Good Hope. It represented the first documented European passage through the southern tip of the Americas, significantly impacting global navigation and trade routes.

Challenges Faced During the Expedition

Magellan’s voyage was fraught with considerable challenges, highlighting the dangers inherent in early exploration of Antarctica and southern waters. Navigating the strait was a harrowing experience; Magellan’s fleet of five ships faced dangerous weather conditions, strong currents, and narrow channels that required meticulous steering.

Additionally, frigid temperatures and a lack of fresh provisions threatened the crew’s survival. Mutiny also disrupted the expedition, as the immense difficulties and prolonged isolation tested the crew’s morale. By the time the fleet emerged into the Pacific Ocean, only three of the original ships remained intact, and Magellan’s fleet was significantly weakened.

The Pacific crossing further challenged the expedition, as Magellan underestimated its vastness. The crew endured extreme privations, including scurvy and starvation, with limited fresh food or water. Magellan himself was ultimately killed in the Philippines, and only one ship, the Victoria, completed the circumnavigation, returning to Spain in 1522 under the command of Juan Sebastián Elcano.

Historical Importance and Legacy of Magellan’s Discovery

Magellan’s journey marked a pivotal point in maritime history. The discovery of the Strait of Magellan had immediate and lasting significance for European expansion, enabling a western route to the Pacific and Asia. Though complex and perilous, the strait became a valuable channel for navigation until the construction of the Panama Canal in the early 20th century. The expedition’s success not only proved the feasibility of global circumnavigation but also spurred further exploration, eventually leading to voyages that approached Antarctica’s icy shores.

The legacy of Magellan’s discovery is interwoven with the early exploration of Antarctica and the Southern Hemisphere. His voyage illustrated both the strategic importance and the considerable dangers of exploring the southern oceans. While he did not reach Antarctica, Magellan’s navigation of the strait set the stage for future expeditions southward, inspiring centuries of maritime exploration that ultimately led to the Antarctic continent’s discovery.

In summary, Magellan’s journey across the strait was a landmark in early exploration, expanding European understanding of the globe and establishing a navigable route in the challenging southern waters. His achievements laid the groundwork for future explorers to venture further into the uncharted regions of the southern seas, contributing to the broader legacy of human exploration and discovery.

Sir Francis Drake’s Circumnavigation (1577–1580): Opening New Frontiers in Early Exploration of Antarctica and the Southern Hemisphere

Sir Francis Drake’s circumnavigation from 1577 to 1580 stands as one of the most consequential voyages of early modern exploration. Sponsored by Queen Elizabeth I, Drake’s mission sought not only to establish new trade routes but also to undermine Spanish influence by exploring southern waters previously untouched by English explorers. His journey, which included a notable passage through the Strait of Magellan, significantly impacted the early exploration of Antarctica and the wider southern oceans, pushing European knowledge of the Southern Hemisphere into new realms.

Mission Objectives and Journey Southward

Queen Elizabeth I commissioned Drake’s expedition with two principal objectives: to disrupt Spanish holdings in the Americas and to expand English maritime presence in the Pacific. Although early exploration of Antarctica was not part of the explicit agenda, Drake’s route took him into previously uncharted southern waters that brought him within close proximity of the southern polar regions.

Departing Plymouth in December 1577, Drake navigated along the eastern coast of South America, eventually reaching the Strait of Magellan in 1578. Here, his fleet faced its first major test in the turbulent strait, where the unpredictability of southern weather posed significant navigational challenges. Passing through the strait marked Drake as the second European navigator to use this route after Magellan, solidifying England’s claim to southern oceanic exploration.

Severe Challenges in the Southern Oceans

After navigating through the Strait of Magellan, Drake’s fleet encountered a series of unforeseen obstacles that tested the endurance of the crew. Upon reaching the Pacific, violent storms scattered his fleet, and only his flagship, the Golden Hind, survived. This separation drove Drake further southward along the Pacific coast, where he inadvertently reached what is now known as Cape Horn, effectively exploring the southern tip of South America.

Though he did not sight Antarctica, these waters put him closer to the continent than any previous European navigator, contributing indirectly to early exploration of Antarctica by confirming the open ocean south of Tierra del Fuego.

The expedition’s hardships underscored the risks of exploring the uncharted Southern Hemisphere. The extreme cold, hazardous waters, and unpredictable winds forced Drake to employ cautious navigation. His encounter with these conditions furthered understanding of the geographic and climatic barriers in the region, influencing future southern expeditions.

Legacy and Impact on Southern Exploration

Drake’s circumnavigation had profound implications for early exploration of Antarctica and the Southern Hemisphere. By venturing into the waters south of Tierra del Fuego, Drake’s journey suggested that a vast, open ocean extended southward, fuelling speculation about an unknown southern land.

While he did not reach Antarctica, his expedition brought European explorers closer to its vicinity and laid the groundwork for subsequent southern voyages. The journey challenged prevailing notions of global geography and provided critical insight into the formidable natural conditions of the far south.

Drake’s successful circumnavigation also demonstrated England’s capability to compete in global exploration, challenging Spain’s dominance over Pacific routes. His route inspired later English expeditions that would continue probing into the Southern Hemisphere, inching closer to the Antarctic continent. Moreover, Drake’s navigation near Cape Horn offered an alternative to the Strait of Magellan, which became essential for future navigators facing the strait’s treacherous waters.

Francis Drake’s circumnavigation extended the boundaries of European knowledge in the Southern Hemisphere, indirectly advancing early exploration of Antarctica by paving the way for deeper southern exploration. His achievements not only established England’s presence in the Pacific but also stimulated further interest in the unexplored southern oceans.

Dutch Exploration of the Southern Ocean: (1599–1643)

The Dutch explorations of the Southern Ocean in the early 17th century mark a significant era in maritime history, as they sought new trade routes, territorial claims, and answers to geographical mysteries. Among these expeditions, the voyages of Dirk Gerritsz in 1599 and Abel Tasman in (portrait below) 1642–1643 are particularly notable for advancing early exploration of the Southern Ocean. These Dutch expeditions not only provided insight into southern waters but also influenced subsequent European exploration, indirectly setting a foundation for Antarctic discovery.

Dirk Gerritsz and the Gerritsz Archipelago

The earliest documented Dutch encounter with the Southern Ocean occurred in 1599, led by Dirk Gerritsz. While en route to the East Indies as part of a larger trade mission, Gerritsz reportedly encountered ice-laden seas south of the Strait of Magellan.

Some accounts suggest he sighted snow-covered land, which later speculation linked to the northern fringes of Antarctica or nearby islands in the Drake Passage, often referred to as the “Gerritsz Archipelago.” This sighting, however, remains debated among historians, with few concrete records. Regardless, the incident marked a critical step in early exploration of the Southern Ocean, raising European awareness of icy territories south of known trade routes.

Though Gerritsz did not pursue further southern exploration, his report influenced Dutch navigators and cartographers. It also contributed to the broader European interest in a possible southern continent, or *Terra Australis Incognita*, which remained a prominent yet unproven geographical concept in the 16th and 17th centuries. Gerritsz’s encounter underscored the extreme conditions of the Southern Ocean, later verified by other navigators venturing into these regions.

Abel Tasman’s Historic Journey: Expanding Dutch Knowledge of the South

Abel Tasman’s expedition of 1642–1643 represented a critical Dutch effort to explore southern waters in search of new territories and potential trade routes. Commissioned by the Dutch East India Company (VOC), Tasman’s primary mission was to find new lands south and east of the East Indies that might expand Dutch influence. Setting sail from Batavia (modern Jakarta), Tasman’s voyage covered vast and uncharted territories in the Southern Hemisphere.

During this journey, Tasman sailed farther south than any previous Dutch expedition, reaching what is now Tasmania, followed by the western coast of New Zealand. He did not encounter Antarctica, though his navigation into higher southern latitudes brought him within relative proximity to its waters. Tasman’s observations of the harsh southern seas and violent weather conditions contributed to European knowledge of the Southern Hemisphere’s challenging environments, while his discoveries expanded Dutch cartographic knowledge and established the Netherlands as a leader in Pacific exploration.

Tasman’s journey proved highly influential in European maps, as his discoveries confirmed new lands south of Java, later known as Tasmania and New Zealand. However, he encountered resistance from local Māori populations in New Zealand, leading him to abandon further exploration of the area. Tasman’s achievements extended Dutch geographical understanding, fostering continued interest in a vast southern land.

The Broader Dutch Impact on Southern Ocean Exploration

The Dutch Republic’s strategic focus on the East Indies led to numerous Dutch expeditions around the Cape of Good Hope, occasionally venturing southward into the Southern Ocean. These missions were primarily driven by trade ambitions, with incidental exploration of southern waters as part of these objectives. While Tasman’s and Gerritsz’s journeys were the most prominent, several other Dutch navigators charted southern latitudes, consolidating Dutch maritime dominance in the 17th century.

Dutch cartography, which reached high levels of precision during this period, furthered European understanding of the Southern Hemisphere. Maps produced by Dutch cartographers, based on explorations like those of Tasman and Gerritsz, included speculative representations of the mysterious southern continent. This portrayal spurred future explorations by the British, French, and Russians, as the existence of *Terra Australis Incognita* remained an unconfirmed but tantalising possibility.

Legacy of Dutch Southern Exploration and Influence on Antarctic Ventures

The Dutch expeditions into the Southern Ocean had enduring influence on the early exploration of Antarctica, though none reached the continent itself. Dirk Gerritsz’s reported sightings and Tasman’s extensive voyages into southern latitudes contributed to the European understanding of the challenging southern environments and raised awareness of lands near the Antarctic region. Tasman’s discoveries encouraged later explorers to probe further south in search of a continent, with his reports shaping future ambitions to explore uncharted polar regions.

The Dutch voyages, through both direct exploration and influential cartography, played an essential role in the collective European interest in the Southern Ocean and Antarctica. While their focus was primarily on trade and territory, the incidental findings of Dutch explorers laid a foundational understanding of the Southern Hemisphere’s geographic realities. This legacy helped propel European expeditions towards the Antarctic, fuelling the desire to unlock the secrets of the frozen southern lands and indirectly paving the way for the continent’s eventual discovery.

Captain James Cook’s First Voyage (1768–1771)

James Cook’s first voyage, commissioned by the British Admiralty and the Royal Society, marked a pivotal moment in the scientific exploration of the Southern Hemisphere. Departing in 1768, Cook’s mission aboard the Endeavour was multifaceted: to observe the transit of Venus from the Pacific and to explore the Southern Ocean in search of the hypothetical southern continent, “Terra Australis”. This voyage significantly expanded European knowledge of the Pacific and the southern seas, bringing Cook closer to Antarctica than any of his predecessors and setting the stage for future Antarctic exploration.

Dual Mission: Scientific Observation and the Quest for Terra Australis

Cook’s first expedition had two principal objectives. The primary scientific aim, supported by the Royal Society, was to observe the transit of Venus across the sun from Tahiti, an event that would aid in calculating the Earth’s distance from the sun and improve navigational accuracy. The secondary, covert mission from the British Admiralty was to search for Terra Australis, a vast southern continent that European geographers believed balanced the known landmasses of the Northern Hemisphere.

After establishing an observation post in Tahiti, Cook successfully documented the transit of Venus in 1769. This achievement fulfilled the primary scientific goal, but it was his ensuing search for new southern lands that had the most lasting geographical impact. Cook’s orders directed him further south into uncharted waters, driving his vessel closer to regions previously untouched by European navigators and pushing the boundaries of early exploration of Antarctica.

Exploration of New Zealand and the Southern Ocean

Following the observations in Tahiti, Cook ventured southwest, eventually reaching New Zealand. He spent over six months circumnavigating and mapping New Zealand’s coastline, proving that it was not part of a larger continental mass but rather two distinct islands. This dispelled earlier European theories that New Zealand might be connected to the mythical southern continent.

After charting New Zealand, Cook continued into the Southern Ocean, testing the extent of navigable waters and advancing the early exploration of Antarctica’s vicinity. Despite encountering increasingly cold temperatures and icy seas, Cook remained undeterred, venturing to higher latitudes than any previous European explorer. Although he did not sight Antarctica, his observations provided the most detailed accounts of the southern seas and their challenging conditions, emphasising the extreme cold, formidable storms, and the prevalence of icebergs.

Challenges of Navigating the Southern Hemisphere

Cook’s voyage through the Southern Ocean presented a series of unprecedented navigational challenges. The Endeavour was not originally designed for such harsh conditions, yet Cook and his crew encountered stormy weather, unpredictable currents, and freezing temperatures. Provisions often ran low, and the threat of scurvy—despite preventive measures—posed a continuous health risk for the crew.

Cook’s meticulous attention to navigational detail and his insistence on maintaining rigorous health standards, including a diet rich in anti-scorbutics, mitigated some of these dangers. His command led to innovative measures for improving crew welfare, such as requiring sailors to consume lemon juice and maintain ship cleanliness, significantly reducing the incidence of scurvy and becoming a model for later long-distance voyages.

Legacy and Contribution to Southern Exploration

James Cook’s first voyage did not locate Terra Australis, but it transformed European understanding of the Southern Hemisphere. By circumnavigating New Zealand and charting its islands, Cook provided valuable cartographic knowledge that corrected and expanded European maps. His thorough exploration of the Southern Ocean also established that if Terra Australis existed, it was situated much further south than previously imagined, possibly within the icy confines of Antarctica.

Cook’s achievements had a profound influence on the direction of subsequent exploration. His observations encouraged the British Admiralty and other European powers to consider more ambitious southern expeditions, including Cook’s own second and third voyages, which probed even closer to Antarctica. His records of the challenging oceanic conditions near Antarctica highlighted the difficulties future explorers would face, offering practical insights for those venturing into the polar regions.

In sum, James Cook’s first voyage redefined European perspectives on the Southern Hemisphere and advanced the early exploration of Antarctica’s surrounding seas. His contributions to cartography, scientific observation, and the understanding of southern geography laid the groundwork for later expeditions, cementing his legacy as a transformative figure in the age of exploration. His journey not only expanded the map but also the scope of scientific inquiry and navigational practice in uncharted territories.

Captain James Cook’s Second Voyage (1772–1775)

James Cook’s second voyage, commissioned by the British Admiralty, was one of the first major expeditions dedicated to the search for Antarctica. With previous maps depicting a speculative landmass called “Terra Australis Incognita” at the bottom of the globe, Cook’s mission was to determine whether a large southern continent truly existed. Setting sail on the HMS Resolution and accompanied by the HMS Adventure, Cook pushed further south than any European navigator before him, breaking new ground in the early exploration of Antarctica and transforming European conceptions of the Southern Hemisphere.

Mission to Prove or Dispel the Myth of “Terra Australis”

Cook’s second expedition had a singular focus: to search for the elusive southern continent believed by many European geographers to balance the world’s landmass. Known as “Terra Australis Incognita”, this hypothetical continent had fueled imaginations for centuries, but its existence remained unverified. Tasked by the Admiralty, Cook set out in 1772 to confirm or disprove the idea of a habitable, temperate land in the far south.

Equipped with the Resolution and the Adventure, both specially prepared for icy conditions, Cook sailed with a seasoned crew and state-of-the-art navigation equipment, including the latest chronometers for precise longitude measurements. His objective was clear: if Terra Australis existed, he was to locate and chart its coastlines. His search would lead him to uncharted waters, enduring frigid conditions, icy seas, and harsh weather.

Pushing the Boundaries of Southern Latitude

During his second voyage, Cook ventured into latitudes previously untested by European navigators, crossing the Antarctic Circle multiple times. In January 1773, Cook became the first recorded explorer to cross the Antarctic Circle, a feat that had long eluded earlier navigators. This crossing marked a historic moment in the exploration of Antarctica, as Cook and his crew faced icy waters filled with icebergs, some towering higher than their ships.

Despite relentless efforts, Cook encountered only the vast Southern Ocean. Each time he crossed further south, he met impassable walls of ice, compelling him to turn back. In his attempts, Cook reached as far south as 71°10′ S, a record at the time. His descriptions of the extreme cold, enormous icebergs, and vast expanses of floating sea ice discouraged the idea of a temperate, inhabited southern continent. Cook came to suspect that if any landmass existed in the far south, it lay under inhospitable, frozen conditions, far from habitable latitudes.

Confronting the Perils of the Southern Ocean

Cook’s expedition through the Southern Ocean was fraught with unprecedented challenges, highlighting the severe conditions of high southern latitudes. The journey involved encounters with dense ice fields, unpredictable storms, and freezing temperatures that strained both ships and crew. Icebergs posed constant threats, requiring vigilant navigation to avoid collisions, while frigid waters and snowstorms reduced visibility, making even basic manoeuvring hazardous.

Health issues, notably the risk of scurvy, remained a concern throughout the voyage. However, Cook’s insistence on dietary measures, including citrus juice and fresh provisions when possible, helped maintain crew health and provided a benchmark for future long-duration voyages. His management practices set new standards for sustaining human life in extreme environments and demonstrated the vital importance of careful preparation in polar exploration.

Redefining the Concept of Antarctica and the Southern Hemisphere

Although Cook did not sight the Antarctic continent, his voyage effectively redefined European ideas about the far south. His repeated encounters with impenetrable ice led him to conclude that “Terra Australis” was either nonexistent or confined to a frozen, uninhabitable region. His report cast doubt on centuries-old myths of a lush southern land and reshaped the goals of future explorers, encouraging them to pursue scientific inquiry over territorial ambitions.

Cook’s findings provided invaluable data on the Southern Ocean’s climate, sea currents, and ice conditions, laying a foundation for future Antarctic expeditions. By debunking the notion of a warm, populated southern continent, Cook redirected the focus of polar exploration, ultimately steering later explorers toward the Antarctic as a region of scientific interest rather than a land of potential settlement.

Legacy of Cook’s Antarctic Exploration

James Cook’s second voyage marked a transformative moment in the early exploration of Antarctica and polar science. While he did not confirm the existence of a continental landmass, his achievements went beyond physical discovery. Cook’s comprehensive charts of the Southern Ocean, meticulous observations of ice formations, and encounters with formidable conditions provided future explorers with essential knowledge about the Antarctic environment. His conclusions shifted the ambitions of European explorers, preparing the way for scientific expeditions in the 19th century that would further probe Antarctica’s mysteries.

Cook’s expedition remains a landmark in Antarctic history, showcasing the immense challenges of southern exploration and the endurance required to push human knowledge to its limits. By demonstrating the Southern Ocean’s vast, icy expanse, he helped dispel myths and solidified the idea of Antarctica as a frozen, remote part of the Earth—a place of natural wonder and extreme conditions rather than habitable lands.

First Confirmed Sightings of the Antarctic Continent (1820–1821)

The years 1820 and 1821 mark a pivotal period in the early exploration of Antarctica, with expeditions led by Fabian von Bellingshausen, Edward Bransfield, and John Davis each contributing to the first confirmed sightings and charting of the Antarctic continent. These voyages, driven by a mix of scientific curiosity, national pride, and strategic interest, laid the foundations for modern Antarctic exploration by revealing the existence of the southern polar landmass.

Fabian von Bellingshausen: Russian Expedition (1820)

Under the command of Fabian von Bellingshausen, the Russian Antarctic expedition of 1820 became one of the earliest recorded voyages to sight the Antarctic continent. Commissioned by Tsar Alexander I, Bellingshausen’s mission involved exploring the southern polar seas to locate and potentially claim new territories for Russia. Sailing aboard the sloop Vostok, accompanied by the Mirny under the command of Mikhail Lazarev, Bellingshausen’s expedition represented Russia’s first significant attempt to engage in southern ocean exploration and the search for Antarctica.

On January 27, 1820, Bellingshausen’s expedition sighted what is now recognised as part of the Antarctic mainland, near Queen Maud Land. His sighting of an ice-covered landmass south of 69°21′ S is widely regarded as the first confirmed encounter with the Antarctic continent. Bellingshausen’s detailed logs and observations marked this event, with later analysis confirming that his sighting included parts of the Antarctic mainland rather than surrounding islands. Despite harsh weather and limited visibility, Bellingshausen’s persistence allowed him to observe and chart significant portions of the Antarctic ice.

Bellingshausen’s expedition made further progress in southern waters, circling the continent twice and mapping portions of the Antarctic ice shelf. His voyage contributed substantially to early Antarctic charting, recording vital data on ice conditions, weather, and oceanic features. Although his achievements remained relatively unknown in Western Europe for some time, Bellingshausen’s sighting of the continent set a precedent for later explorers and confirmed that a substantial landmass lay beneath the icy southern ocean.

Edward Bransfield: The British Expedition (1820)

In the same year as Bellingshausen’s sighting, the British navigator Edward Bransfield embarked on an expedition that added to the early exploration of Antarctica. Tasked by the British Admiralty to explore southern waters, Bransfield’s journey originated from the South Shetland Islands, where recent sightings of icebergs and isolated islands had piqued British interest. Sailing aboard the Williams, Bransfield’s mission was to investigate the region further, with an emphasis on mapping and claiming new lands for Britain.

On January 30, 1820, Bransfield sighted the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, becoming one of the first navigators to encounter and document the continent’s landmass. His observations, recorded along the coast of what is now Trinity Peninsula, included detailed notes on the landscape, ice formations, and coastal features. Bransfield’s encounter with the Antarctic Peninsula represented the first confirmed British sighting of the Antarctic continent, although his findings remained largely unpublicised at the time.

Bransfield’s charts and descriptions provided essential geographic information for future expeditions, offering insight into the extreme conditions and rugged terrain of the Antarctic Peninsula. His findings underscored the challenging nature of the region, marked by harsh weather, ice-filled waters, and inhospitable landscapes. Although he did not explore further into the continent, Bransfield’s observations contributed significantly to early Antarctic mapping and affirmed Britain’s interest in southern exploration.

John Davis: The American Sealer’s Landing (1821)

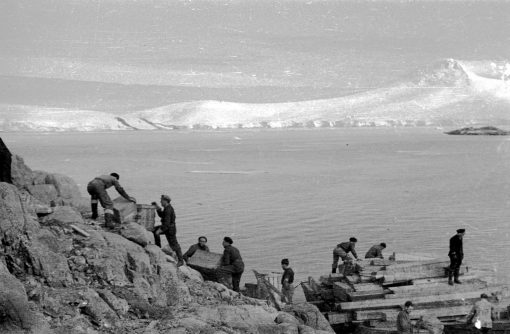

The following year, in 1821, American sealer John Davis made what is believed to be the first confirmed landing on the Antarctic continent. Aboard the Cecilia, Davis operated primarily as a sealer, pursuing lucrative fur seal populations around the South Shetland Islands and nearby regions. Although his primary aim was commercial, Davis’s venture into southern waters led him close to the Antarctic coast, where he made a brief but significant landing.

On February 7, 1821, Davis recorded a landing at Hughes Bay on the Antarctic Peninsula. His landing is considered the earliest confirmed instance of humans setting foot on the Antarctic continent, though some details of the event remain debated among historians. Davis’s journal entry noted the inhospitable conditions and the icy landscape, yet he made no extensive exploration beyond the initial landing, returning promptly to his ship due to the severe weather and logistical challenges.

Davis’s landing underscored the dangers inherent in Antarctic exploration. As a sealer, his priorities were more economic than scientific, yet his landing represents a milestone in Antarctic exploration. This brief encounter confirmed that reaching the Antarctic continent was feasible, albeit under challenging and often hazardous conditions. His account provided an early glimpse into the immense difficulties posed by the region’s ice-laden environment, setting the stage for later scientific expeditions.

Legacy of the First Sightings and Charting of Antarctica

The voyages of Bellingshausen, Bransfield, and Davis collectively mark the beginning of confirmed Antarctic exploration. Each expedition, despite differing motivations and national backgrounds, contributed unique insights into the existence, geography, and conditions of the Antarctic continent. Bellingshausen’s comprehensive charting, Bransfield’s detailed observations of the Antarctic Peninsula, and Davis’s historic landing each provided early evidence of the continent’s presence and began to dispel myths of a temperate southern land.

These early sightings and chartings paved the way for later scientific and exploratory missions. By verifying the existence of an icy continent, these explorers established Antarctica as a new frontier, attracting interest from scientists and explorers across Europe and North America. The knowledge they gathered on ice conditions, coastlines, and the harsh environment advanced human understanding of the polar regions, influencing subsequent expeditions in the 19th and 20th centuries.

In sum, the expeditions of Bellingshausen, Bransfield, and Davis set foundational milestones in the early exploration of Antarctica. Their discoveries confirmed the existence of the southern polar landmass, dispelling previous myths and initiating a new era of Antarctic exploration driven by both scientific and territorial ambitions.

Further Exploration and Mapping of Antarctica (1839–1893)

The mid-19th to late-19th centuries saw significant advancements in the early exploration of Antarctica, with expeditions led by James Clark Ross, HMS Challenger, and Carl Anton Larsen contributing to further mapping and understanding of the southern polar region. Each expedition, driven by distinct goals yet united in its pursuit of new knowledge, expanded the boundaries of Antarctic exploration and provided valuable data that would shape future expeditions.

James Clark Ross: Mapping Antarctic Waters and Discovering the Ross Sea (1839–1843)

The British Antarctic Expedition led by James Clark Ross between 1839 and 1843 represented one of the earliest and most comprehensive missions focused on the mapping and exploration of Antarctica. Commanding the ships Erebus and Terror, Ross embarked on an ambitious journey to investigate Earth’s magnetic field near the magnetic south pole, while also expanding British geographic knowledge of the Southern Ocean and the Antarctic coastline. Ross’s mission brought him into uncharted waters, pushing the frontiers of Antarctic exploration farther than any previous expedition.

During his voyage, Ross made several historic discoveries, including the vast Ross Sea and the towering volcanic mountains of Mount Erebus and Mount Terror, named after his ships. In 1841, his ships entered the ice-laden Ross Sea, allowing him to explore the extensive ice shelf now known as the Ross Ice Shelf. Ross meticulously charted this ice shelf, which extended hundreds of kilometres across the coastline, providing the first detailed records of this major Antarctic feature. His observations included the structure and behaviour of pack ice, critical data for understanding Antarctic ice dynamics.

Ross’s contributions to the early exploration of Antarctica were profound, as his expedition not only expanded knowledge of Antarctic waters but also confirmed the existence of substantial land masses and ice shelves. His charts and observations would serve as vital resources for future Antarctic expeditions, establishing foundational geographic information about the continent and its surrounding seas. Ross’s work significantly enhanced European understanding of the southern polar environment, setting a standard for scientific exploration in Antarctica.

HMS Challenger: Scientific Investigations in the Southern Ocean (1872–1876)

The voyage of HMS Challenger, a pioneering scientific expedition from 1872 to 1876, marked a transformative moment in the study of the world’s oceans, including the Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica. Sponsored by the British government and the Royal Society, this expedition aimed to conduct a comprehensive scientific survey of oceanic conditions, deep-sea organisms, and marine geology. Although not explicitly tasked with charting the Antarctic continent, the Challenger nonetheless made substantial contributions to the early exploration of Antarctica by gathering unprecedented scientific data on Antarctic waters.

Sailing into the icy southern latitudes, the Challenger recorded the ocean’s depth, water temperature, and salinity, providing foundational data for understanding the Southern Ocean’s unique characteristics. The expedition confirmed that the Southern Ocean was significantly colder and deeper than other seas, with a unique ecosystem adapted to extreme conditions. This information was essential for later Antarctic exploration, as it helped navigators prepare for the environmental challenges of high southern latitudes.

The Challenger expedition also made a considerable impact on marine biology, cataloguing species that thrived in cold, nutrient-rich waters and documenting unique Antarctic life forms, such as krill. By revealing the abundance of marine life in these icy seas, the expedition underscored the ecological significance of the Southern Ocean. The findings from HMS Challenger laid the groundwork for scientific interest in Antarctic marine ecosystems, encouraging later expeditions to investigate the continent’s biological and geological significance.

Carl Anton Larsen: Exploring the Antarctic Peninsula and Larsen Ice Shelf (1892–1893)

In 1892–1893, Norwegian explorer Carl Anton Larsen led an expedition that ventured further into the Antarctic Peninsula region, making significant strides in mapping and exploring the coastline and identifying new geographical features. Commanding the whaling ship Jason, Larsen’s expedition combined scientific inquiry with commercial interests, seeking to map potential whaling grounds and locate new coastal areas for whaling operations. His journey brought him into direct contact with the Antarctic Peninsula’s eastern coast, where he documented significant features of the landscape and ocean.

Larsen made a historic landing on the Antarctic continent in 1893, one of the earliest recorded landings in the area, marking a new step in the early exploration of Antarctica. During his exploration of the Antarctic Peninsula’s eastern coast, Larsen observed a vast ice shelf, later named the Larsen Ice Shelf in his honour. His descriptions and charts of this ice shelf were some of the first detailed accounts of the region’s extensive glacial formations, contributing valuable information to the broader geographic and scientific understanding of Antarctica’s structure.

Larsen’s expedition also highlighted the commercial potential of the Antarctic region, particularly for whaling and sealing. His observations of abundant marine life supported early economic interest in Antarctic resources, foreshadowing the commercial whaling industry that would soon expand into Antarctic waters. Although primarily a commercial venture, Larsen’s journey contributed meaningfully to Antarctic exploration by mapping portions of the peninsula and providing early descriptions of the Larsen Ice Shelf and surrounding regions.

Legacy of Early Mapping and Scientific Exploration in Antarctica

The expeditions of Ross, HMS Challenger, and Carl Anton Larsen collectively advanced the early exploration of Antarctica, each bringing new insights into the continent’s geography, climate, and ecosystems. Ross’s meticulous mapping of the Ross Sea and Ross Ice Shelf established a geographic framework that would guide future Antarctic missions, while the Challenger’s scientific investigations illuminated the unique conditions and marine biodiversity of the Southern Ocean. Larsen’s exploration of the Antarctic Peninsula and discovery of the Larsen Ice Shelf added to the mapping of Antarctica’s coastlines, strengthening European knowledge of this remote region.

These expeditions laid the foundation for the 20th-century scientific missions that would eventually conduct in-depth exploration of Antarctica. By mapping key geographic features and recording valuable scientific data, these early explorers expanded global understanding of the Antarctic continent and the surrounding Southern Ocean, fostering a legacy of scientific and geographic discovery that continues to drive Antarctic exploration today.

Further reading

The Royal Museum Greenwich has more information on the early exploration of Antarctica.